Can You Save One Species by Annoying Another?

In “Eco-Hack!,” the filmmakers Brett Marty and Josh Izenberg document a conservation biologist’s novel strategy for rescuing the desert tortoise: booby traps. Film by Brett Marty and Josh Izenberg Text by Murat Oztaskin.

In “Eco-Hack!,” the filmmakers Brett Marty and Josh Izenberg document a conservation biologist’s novel strategy for rescuing the desert tortoise: booby traps. Film by Brett Marty and Josh Izenberg Text by Murat Oztaskin.

Solar sprawl is tearing up the Mojave Desert

LA Times by Elvia Limón, Kevinisha Walker

Solar panels could save California. But they hurt the desert

Las Vegas has more solar panels per person than any major U.S. metro area outside Hawaii, according to one analysis. There’s an enormous opportunity to lower household utility bills and cut climate pollution — without damaging wildlife habitat or disrupting treasured landscapes.

But that hasn’t stopped corporations from making plans to carpet the desert surrounding Las Vegas with dozens of giant solar fields — some of them designed to supply power to California. The Biden administration has fueled that growth.

Those energy generators could imperil rare plants and slow-footed tortoises already threatened by rising temperatures. They could also lessen the death and suffering from the climate crisis.

Read the article here: https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2023-06-27/solar-panels-could-save-california-but-they-hurt-the-desert

LA Times by Elvia Limón, Kevinisha Walker

Solar panels could save California. But they hurt the desert

Las Vegas has more solar panels per person than any major U.S. metro area outside Hawaii, according to one analysis. There’s an enormous opportunity to lower household utility bills and cut climate pollution — without damaging wildlife habitat or disrupting treasured landscapes.

But that hasn’t stopped corporations from making plans to carpet the desert surrounding Las Vegas with dozens of giant solar fields — some of them designed to supply power to California. The Biden administration has fueled that growth.

Those energy generators could imperil rare plants and slow-footed tortoises already threatened by rising temperatures. They could also lessen the death and suffering from the climate crisis.

Read the article here: https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2023-06-27/solar-panels-could-save-california-but-they-hurt-the-desert

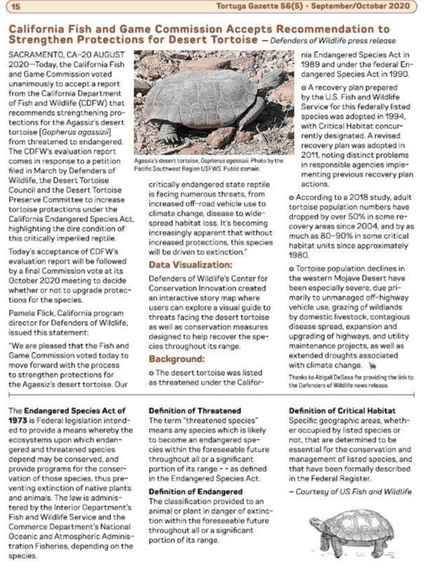

By Emily Thomas, Lead Conservation Biologist

At the end of March, 69 desert tortoise hatchlings, who were housed at The Living Desert for the previous seven months, made the big transition from their indoor rearing home at the Tennity Wildlife Hospital to their outdoor rearing facility at Edwards Air Force Base (EAFB). As we like to say, they graduated! The tortoises’ transition to EAFB is the intermediate step on their journey back out into their native range. In collaboration with San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA), EAFB, and the U.S. Geological Survey, this multi-step headstart program gives the young desert tortoises a better chance for survival by facilitating accelerated growth and hardening their protective shells, leaving the tortoises less vulnerable to predation.

Read the article here: https://issuu.com/the-livingdesert/docs/foxpaws_summer_2023/s/27101824

At the end of March, 69 desert tortoise hatchlings, who were housed at The Living Desert for the previous seven months, made the big transition from their indoor rearing home at the Tennity Wildlife Hospital to their outdoor rearing facility at Edwards Air Force Base (EAFB). As we like to say, they graduated! The tortoises’ transition to EAFB is the intermediate step on their journey back out into their native range. In collaboration with San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA), EAFB, and the U.S. Geological Survey, this multi-step headstart program gives the young desert tortoises a better chance for survival by facilitating accelerated growth and hardening their protective shells, leaving the tortoises less vulnerable to predation.

Read the article here: https://issuu.com/the-livingdesert/docs/foxpaws_summer_2023/s/27101824

This spring, the 69 desert tortoise hatchlings in the headstart program safely transitioned from indoor rearing at The Living Desert Zoo and Gardens to an outdoor rearing facility at Edwards Air Force Base (EAFB)! The tortoises’ transition to EAFB is an intermediate step on their journey back to life on their own in the desert.

Read the full article at:

How Solar Farms Took Over the California Desert:

‘An Oasis Has Become a Dead Sea’

Deep in the Mojave desert, about halfway between Los Angeles and Phoenix, a sparkling blue sea shimmers on the horizon. Visible from the I-10 highway, amid the parched plains and sun-baked mountains, it is an improbable sight: a deep blue slick stretching for miles across the Chuckwalla Valley, forming an endless glistening mirror.

But something’s not quite right. Closer up, the water’s edge appears blocky and pixelated, with the look of a low-res computer rendering, while its surface is sculpted in orderly geometric ridges, like frozen waves.

“We had a guy pull in the other day towing a big boat,” says Don Sneddon, a local resident. “He asked us how to get to the launch ramp to the lake. I don’t think he realized he was looking at a lake of solar panels.”

Read the full article at:

But something’s not quite right. Closer up, the water’s edge appears blocky and pixelated, with the look of a low-res computer rendering, while its surface is sculpted in orderly geometric ridges, like frozen waves.

“We had a guy pull in the other day towing a big boat,” says Don Sneddon, a local resident. “He asked us how to get to the launch ramp to the lake. I don’t think he realized he was looking at a lake of solar panels.”

Read the full article at:

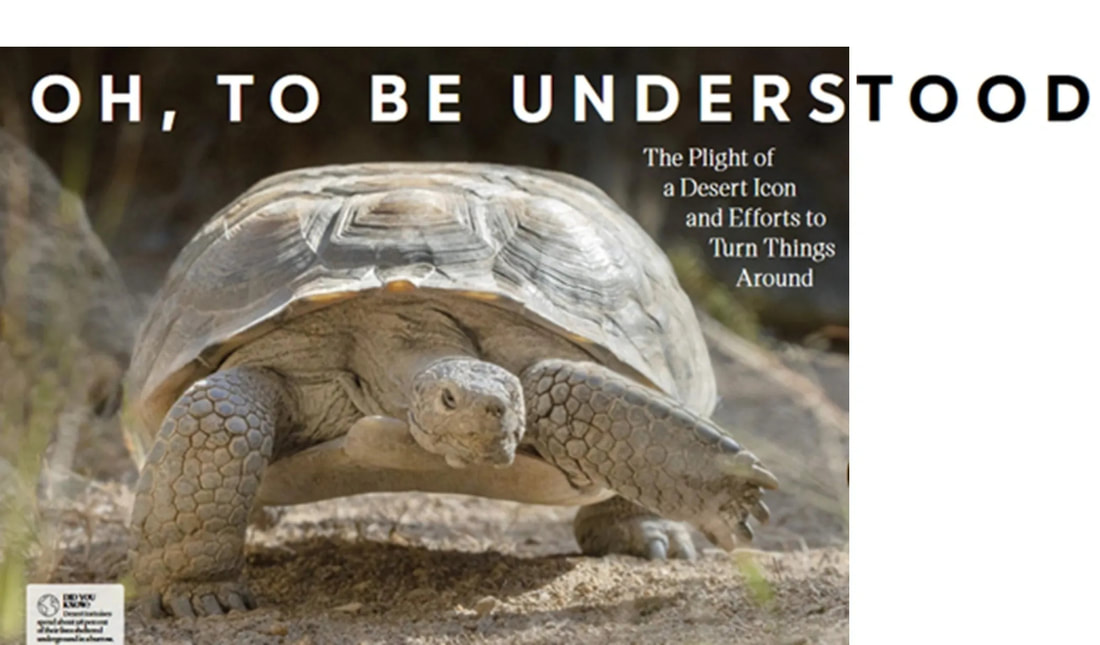

Even the Hardy Desert Tortoise Needs Help

as the Earth Warms and Habitat Disappears

EDWARDS AIR FORCE BASE, Calif. — Joshua trees and creosote brush poke up through the rocky earth of the Mojave Desert on an early spring afternoon. Mount Baldy towers in the distance, its snow-capped peak contrasting with the low, dry conditions on Edwards Air Force Base, where a field team of ecologists and wildlife specialists are bringing a rare species to their future home.

The wind whips through the brush as the team starts its work. Members of the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance wear green ball caps and a team from the Living Desert Zoo and Gardens sport matching windbreakers. Their hands wrapped in blue latex gloves, they carry gray plastic bins from the trunk of an SUV. Each container holds about six of the 69 desert tortoises that came from the zoo. They make their way to the outdoor “head start” pens on the base.

“All of us are very proud,” said Emily Thomas, conservation biologist at the Living Desert Zoo and Gardens, based in Palm Desert. “It’s exciting seeing them move on to the next stage in their journey before their release in these bigger habitats.”

There are two desert tortoise species in the Southwest: the Sonoran, which is most common east and south of the Colorado River, and the Mojave, found west and north of the river. The team at Edwards is focused on bringing the Mojave tortoise back to its natural landscape.

One of the desert's most iconic denizens, the tortoise, has been in peril for decades, its numbers declining as its range shrinks due to habitat loss and fragmentation. Infectious disease, vehicle strikes and rising temperatures have also affected the species' struggle for survival. The Mojave species is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The goal of the tortoise program is to give the species a fighting chance by providing a safe environment during the most vulnerable stage of life. Team members from both the wildlife alliance and the zoo have been caring for this group of young desert tortoise hatchlings for the past six months and will continue to monitor the tortoises until they are ready for a full release into the wild.

How heat affects hardy desert species

Once common throughout the deserts of the Southwest, Mojave desert tortoise populations have declined by an estimated 90% in the last 20 years. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s evaluation of population trends from 2018 indicate that the species is on a path to extinction under current conditions.

Last year, the wildlife alliance tracked a group of gravid adult females at Edwards Air Force Base, about 90 miles north of Los Angeles. The females were taken to outdoor rearing pens, where a field team monitored them and conducted behavioral trials. Once the females laid their eggs, they were returned to the wild.

A typical clutch for a female tortoise contains four to eight eggs. The clutches were meant to hatch at the outdoor pens and then brought to the Living Desert Zoo and Gardens, where they would be able to grow more than twice the size that they would in the wild.

But after nests began to emerge during a dangerous heat wave last fall, biologists excavated the eggs and partial hatchlings and moved them to the zoo early.

“Hatchlings were emerging from their nest in the heat wave,” said Mellissa Merrick, associate director of recovery ecology for the wildlife alliance. “And that caused us a lot of concern and that is one of the reasons we moved them to the Living Desert one month ahead of schedule.”

Although desert tortoises are well adapted to high temperatures, much is not understood about the effects of extended extreme heat on hatchlings in the wild. Rising temperatures over the last few decades is cause for concern by experts because young tortoises already have a high mortality rate. Around 95% of desert tortoises in the wild do not survive the first five years, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Tortoise eggs stop developing when the outdoor temperature reaches around 96 degrees Fahrenheit. Their upper critical maximum capacity is 109 degrees. At that point cognitive function is impaired and death could follow. It was around that temperature when hatchings began to emerge from their nest last fall.

“Obviously tortoises experience temperatures that are that hot on a regular basis and they have the capacity to use shelter sites and burrow to mitigate,” Merrick said. “But hatchlings are much smaller, and thermoregulation is harder for them because they don’t have any sort of thermal inertia.”

Adult tortoises are more equipped to handle high temperatures, as their larger mass allows for them to release heat faster. Smaller and young tortoises have difficulty adapting to the extreme temperatures found in the Mojave Desert, and longer and hotter summers are making recovery more difficult to manage.

Adopting tortoises in Arizona

On the other side of the Colorado River, Arizona Game and Fish Department and the Arizona Tortoise Rescue work to find homes for the vulnerable and threatened species.

Each year the state agency adopts out hundreds of captive Sonoran desert tortoises that are surrendered to the department. The tortoises cannot be released back into the wild because captive tortoises can transmit diseases that could decimate wild populations.

“We take in captive desert tortoises from all over the state and try to find new homes for them,” said Tegan Wolf, desert tortoise adoption program coordinator “We have close to 200 right now.”

Wolf says most of the tortoises come from illegal breeding activities or from people who can no longer care for their tortoises. In the last 10 years, the program has grown as the public becomes more aware of adoption. Last year the program received more than 400 tortoises.

Many of the tortoises the program has received in recent years are juveniles since they are coming from illegal breeding. Wolf says it has been a challenge to adopt out the young because of the long-term commitment. The tortoises can live to be up to 80 years old.

“We have a lot of little ones who need home,” “It’s the opposite with dogs and cats, the adults are more popular than the babies,” Wolf said.

The remote quiet of an Air Force base offers a haven

The San Diego Wildlife Alliance has been involved in desert tortoise research for the last 13 years. The program has focused on jump-starting populations in decline. The time the hatchlings spend under the care of the team helps get them through their most vulnerable stage of life.

Hatchlings are typically no more than two and half inches in length, which makes them an easy target for predators like ravens and coyotes. But part of the process of monitoring young hatchlings is to understand how different habitat characteristics influence their survival and growth once they are released.

The shelter and vegetation at Edwards Air Force Base make it an ideal home for the species. The area’s remote surroundings give the reptile a better chance for survival. With few exceptions, the area is largely uninhabited, which limits human-caused disturbances like traffic, new housing, and illegal killings.

Tortoises also prefer the rocky substrate found in the area over a prominently sandy environment, partly because the rocky cover provides camouflage for young. Juvenile tortoises use their size to blend in with small rocks found in the desert to deter predators.

Merrick said the area is also desirable for tortoises because of mounds that are formed when sand is blown and captured by shrubs. When these mounds form, the soil underneath becomes more friable for small mammals, like desert woodrats or cottontails, to dig into, which creates pre-made burrows suitable for young tortoises.

“It has this cool little microhabitat, where the shrub presence promotes a little community of small mammals that use that area to make burrows,” she said. “The little tortoises are about that size and fit really well into those burrows.”

Hatchlings from the Living Desert will be kept in managed care for another six months at the head start facility. The outdoor pens are covered by a net top to prevent predation. Before they are released into the wild, tortoises will be fitted with a radio transmitter to allow the team to track their movements.

Team will monitor the tortoises in the wild

Monitored care is wildly important for a species that has been threatened in recent in decades. And even fewer young tortoises have been found in their range over the last 20 years, largely due to habitat fragmentation.

Urban development pushing into the desert has not only destroyed potential habitat for tortoises but has pushed predators into new territory as well. New structures give a heightened advantage to birds of prey that now have ready-made perches to look for their next meal.

“As communities in the desert continue to grow and expand, there’s other infrastructure with that like powerlines, billboards, and roadkill,” Merrick said. “And all of that provides additional resources to predators like ravens and coyotes to allow them to persist at densities that are unnatural to what they were in the past before humans became so prominent on the landscape.”

Desert tortoises take nearly 20 years to reach sexual maturity, which is why intervening at a young age is so important. “One thing we could do to get them past that most vulnerable stage is to raise the young up from a couple years to make sure they are a bit bigger, and their shells are harder,” Merrick said. “By selecting careful release sites, it might provide more cover and just another little boost.”

The team will also investigate how nest placement and the resulting temperatures will affect sex ratios. Desert tortoises have temperature-dependent sex determination: Cooler temperatures result in male clutches and warmer temperatures result in female clutches.

“They can make decisions on where they put their nest, how deep they make their nest, and how far deep into the burrow they place their nest,” Merrick said. “And that may be in response to the current temperatures they are experiencing.”

The team has placed temperature sensors on juvenile tortoises, sub-adult, and adult female tortoises to look at how they are using burrows to thermoregulate throughout the day as a function of temperature. Merrick says this will offer a glimpse into how different thermoregulation strategies may vary dependent on age and size.

At the base site, the team carefully places the young tortoises one-by-one into the head start pens, where they begin to acclimate to their new home for the next few months. The tortoises nibble on small plants sprouting from the dirt, acclimating to their new home without hesitation.

It is a bittersweet moment for the team members who raised these tortoises from birth, a moment similar to parents dropping off their child to freshman year of college. It is a new beginning for the young, who are now more prepared to face the harsh elements of the Mojave Desert.

The wind whips through the brush as the team starts its work. Members of the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance wear green ball caps and a team from the Living Desert Zoo and Gardens sport matching windbreakers. Their hands wrapped in blue latex gloves, they carry gray plastic bins from the trunk of an SUV. Each container holds about six of the 69 desert tortoises that came from the zoo. They make their way to the outdoor “head start” pens on the base.

“All of us are very proud,” said Emily Thomas, conservation biologist at the Living Desert Zoo and Gardens, based in Palm Desert. “It’s exciting seeing them move on to the next stage in their journey before their release in these bigger habitats.”

There are two desert tortoise species in the Southwest: the Sonoran, which is most common east and south of the Colorado River, and the Mojave, found west and north of the river. The team at Edwards is focused on bringing the Mojave tortoise back to its natural landscape.

One of the desert's most iconic denizens, the tortoise, has been in peril for decades, its numbers declining as its range shrinks due to habitat loss and fragmentation. Infectious disease, vehicle strikes and rising temperatures have also affected the species' struggle for survival. The Mojave species is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The goal of the tortoise program is to give the species a fighting chance by providing a safe environment during the most vulnerable stage of life. Team members from both the wildlife alliance and the zoo have been caring for this group of young desert tortoise hatchlings for the past six months and will continue to monitor the tortoises until they are ready for a full release into the wild.

How heat affects hardy desert species

Once common throughout the deserts of the Southwest, Mojave desert tortoise populations have declined by an estimated 90% in the last 20 years. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s evaluation of population trends from 2018 indicate that the species is on a path to extinction under current conditions.

Last year, the wildlife alliance tracked a group of gravid adult females at Edwards Air Force Base, about 90 miles north of Los Angeles. The females were taken to outdoor rearing pens, where a field team monitored them and conducted behavioral trials. Once the females laid their eggs, they were returned to the wild.

A typical clutch for a female tortoise contains four to eight eggs. The clutches were meant to hatch at the outdoor pens and then brought to the Living Desert Zoo and Gardens, where they would be able to grow more than twice the size that they would in the wild.

But after nests began to emerge during a dangerous heat wave last fall, biologists excavated the eggs and partial hatchlings and moved them to the zoo early.

“Hatchlings were emerging from their nest in the heat wave,” said Mellissa Merrick, associate director of recovery ecology for the wildlife alliance. “And that caused us a lot of concern and that is one of the reasons we moved them to the Living Desert one month ahead of schedule.”

Although desert tortoises are well adapted to high temperatures, much is not understood about the effects of extended extreme heat on hatchlings in the wild. Rising temperatures over the last few decades is cause for concern by experts because young tortoises already have a high mortality rate. Around 95% of desert tortoises in the wild do not survive the first five years, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Tortoise eggs stop developing when the outdoor temperature reaches around 96 degrees Fahrenheit. Their upper critical maximum capacity is 109 degrees. At that point cognitive function is impaired and death could follow. It was around that temperature when hatchings began to emerge from their nest last fall.

“Obviously tortoises experience temperatures that are that hot on a regular basis and they have the capacity to use shelter sites and burrow to mitigate,” Merrick said. “But hatchlings are much smaller, and thermoregulation is harder for them because they don’t have any sort of thermal inertia.”

Adult tortoises are more equipped to handle high temperatures, as their larger mass allows for them to release heat faster. Smaller and young tortoises have difficulty adapting to the extreme temperatures found in the Mojave Desert, and longer and hotter summers are making recovery more difficult to manage.

Adopting tortoises in Arizona

On the other side of the Colorado River, Arizona Game and Fish Department and the Arizona Tortoise Rescue work to find homes for the vulnerable and threatened species.

Each year the state agency adopts out hundreds of captive Sonoran desert tortoises that are surrendered to the department. The tortoises cannot be released back into the wild because captive tortoises can transmit diseases that could decimate wild populations.

“We take in captive desert tortoises from all over the state and try to find new homes for them,” said Tegan Wolf, desert tortoise adoption program coordinator “We have close to 200 right now.”

Wolf says most of the tortoises come from illegal breeding activities or from people who can no longer care for their tortoises. In the last 10 years, the program has grown as the public becomes more aware of adoption. Last year the program received more than 400 tortoises.

Many of the tortoises the program has received in recent years are juveniles since they are coming from illegal breeding. Wolf says it has been a challenge to adopt out the young because of the long-term commitment. The tortoises can live to be up to 80 years old.

“We have a lot of little ones who need home,” “It’s the opposite with dogs and cats, the adults are more popular than the babies,” Wolf said.

The remote quiet of an Air Force base offers a haven

The San Diego Wildlife Alliance has been involved in desert tortoise research for the last 13 years. The program has focused on jump-starting populations in decline. The time the hatchlings spend under the care of the team helps get them through their most vulnerable stage of life.

Hatchlings are typically no more than two and half inches in length, which makes them an easy target for predators like ravens and coyotes. But part of the process of monitoring young hatchlings is to understand how different habitat characteristics influence their survival and growth once they are released.

The shelter and vegetation at Edwards Air Force Base make it an ideal home for the species. The area’s remote surroundings give the reptile a better chance for survival. With few exceptions, the area is largely uninhabited, which limits human-caused disturbances like traffic, new housing, and illegal killings.

Tortoises also prefer the rocky substrate found in the area over a prominently sandy environment, partly because the rocky cover provides camouflage for young. Juvenile tortoises use their size to blend in with small rocks found in the desert to deter predators.

Merrick said the area is also desirable for tortoises because of mounds that are formed when sand is blown and captured by shrubs. When these mounds form, the soil underneath becomes more friable for small mammals, like desert woodrats or cottontails, to dig into, which creates pre-made burrows suitable for young tortoises.

“It has this cool little microhabitat, where the shrub presence promotes a little community of small mammals that use that area to make burrows,” she said. “The little tortoises are about that size and fit really well into those burrows.”

Hatchlings from the Living Desert will be kept in managed care for another six months at the head start facility. The outdoor pens are covered by a net top to prevent predation. Before they are released into the wild, tortoises will be fitted with a radio transmitter to allow the team to track their movements.

Team will monitor the tortoises in the wild

Monitored care is wildly important for a species that has been threatened in recent in decades. And even fewer young tortoises have been found in their range over the last 20 years, largely due to habitat fragmentation.

Urban development pushing into the desert has not only destroyed potential habitat for tortoises but has pushed predators into new territory as well. New structures give a heightened advantage to birds of prey that now have ready-made perches to look for their next meal.

“As communities in the desert continue to grow and expand, there’s other infrastructure with that like powerlines, billboards, and roadkill,” Merrick said. “And all of that provides additional resources to predators like ravens and coyotes to allow them to persist at densities that are unnatural to what they were in the past before humans became so prominent on the landscape.”

Desert tortoises take nearly 20 years to reach sexual maturity, which is why intervening at a young age is so important. “One thing we could do to get them past that most vulnerable stage is to raise the young up from a couple years to make sure they are a bit bigger, and their shells are harder,” Merrick said. “By selecting careful release sites, it might provide more cover and just another little boost.”

The team will also investigate how nest placement and the resulting temperatures will affect sex ratios. Desert tortoises have temperature-dependent sex determination: Cooler temperatures result in male clutches and warmer temperatures result in female clutches.

“They can make decisions on where they put their nest, how deep they make their nest, and how far deep into the burrow they place their nest,” Merrick said. “And that may be in response to the current temperatures they are experiencing.”

The team has placed temperature sensors on juvenile tortoises, sub-adult, and adult female tortoises to look at how they are using burrows to thermoregulate throughout the day as a function of temperature. Merrick says this will offer a glimpse into how different thermoregulation strategies may vary dependent on age and size.

At the base site, the team carefully places the young tortoises one-by-one into the head start pens, where they begin to acclimate to their new home for the next few months. The tortoises nibble on small plants sprouting from the dirt, acclimating to their new home without hesitation.

It is a bittersweet moment for the team members who raised these tortoises from birth, a moment similar to parents dropping off their child to freshman year of college. It is a new beginning for the young, who are now more prepared to face the harsh elements of the Mojave Desert.

California’s Mojave Desert tortoises move toward extinction. Why saving them is so hard?

CALIFORNIA CITY, Calif. — Behind the fences surrounding this 40-square-mile outback of cactus and wiry creosote, the largest remaining population of Mojave desert tortoises was soaking up the morning sun and grazing on a mix of wild greens and flowers.

Click hyperlink to see the entire article https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2022-11-17/biologists-fear-desert-tortoise-is-headed-for-extinction

Click this hyperlink to view a Los Angeles Times video regarding the Desert Tortoises going extinct: https://youtu.be/5A3HbPhPwq0

CALIFORNIA CITY, Calif. — Behind the fences surrounding this 40-square-mile outback of cactus and wiry creosote, the largest remaining population of Mojave desert tortoises was soaking up the morning sun and grazing on a mix of wild greens and flowers.

Click hyperlink to see the entire article https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2022-11-17/biologists-fear-desert-tortoise-is-headed-for-extinction

Click this hyperlink to view a Los Angeles Times video regarding the Desert Tortoises going extinct: https://youtu.be/5A3HbPhPwq0

Weaponized Juvenile Techno-Tortoises

By Leonie Sherman

March 19, 2023

There was a dead tortoise in my car. She had survived 50 years in the Mojave Desert, the hottest and driest desert in North America, growing from a two-inch hatchling to a fully armored 12-pound beast on a diet of tiny wildflowers, cacti, and dried plants. She and her ancestors had roamed this land for 15 million years, but California's historic drought likely killed her. Tortoise conservationist Tim Shields and I were bringing her carcass to a makerspace in Barstow. There, his company, Hardshell Labs, could create a 3D-printed model of her—a "techno-tort"—that could be used in experimental tortoise conservation.

Along with drought, ravens are a major threat to desert tortoises, having learned that juveniles make a tasty snack (their shells don't fully harden for five to eight years). Though ravens are native to the Mojave Desert, their numbers have exploded as they have followed humans into this inhospitable terrain. "Look at this place from the point of view of a raven," Shields said, gesturing toward the scattered homes and crumbling shacks in the scrubby desert outside Joshua Tree National Park as we drove by. "Ravens in the numbers we're seeing would not hack it out here without humans. The only water in many of these valleys is from humans. They know they can get a drink and some shade at each of these structures. I've seen a couple of roadkills just this morning; each one creates a reliable cafeteria for them." He shook his head and sighed. "Ravens are ecological vacuum cleaners. We've imported mobile, highly motivated, highly intelligent, adaptable predators into prime desert tortoise habitat. It's an eco-systemic disaster."

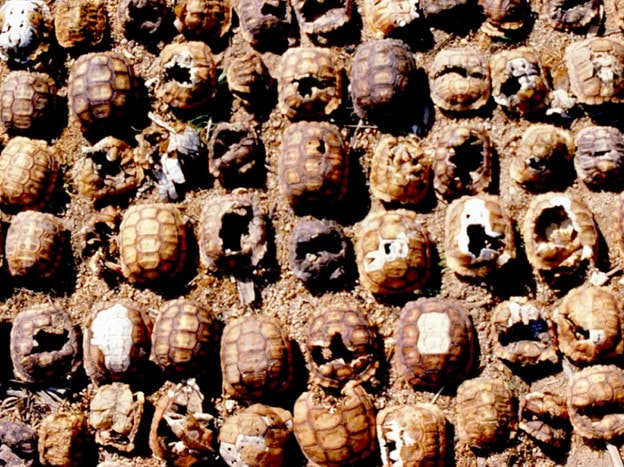

Since Shields began studying these tortoises in 1978, their numbers have declined by 95 percent. One time, a biologist found 136 tortoise corpses under a single raven nest. Once distributed widely through the desert, tortoises now cling to isolated spots in scattered, remote locations. Raven numbers, by contrast, have increased by at least 1,500 percent in the past 40 years. Flocks in the hundreds gather where food, water, and shade are plentiful.

Shields believes that managing ecosystems is now a human obligation. "I sympathize with the sentiment that when humans start messing around with stuff, we screw it up," Shields said. "But I've put hundreds and hundreds of raven-killed baby tortoises into plastic bags. Ravens could wipe tortoises right off the planet and not skip a beat. If we don't do something, if we don't intervene, we will lose the desert tortoise over most of its range. 'Letting nature take its course' means sharing a planet with only domesticated animals and species that that can live off our subsidies."

So Hardshell Labs has pioneered the field of nonlethal avian management, disrupting raven roosting sites and protecting isolated desert tortoise habitat. For example, technicians will station a techno-tort in prime habitat on top of a hidden cylinder. When hungry corvids approach and start pecking at the "shell," they're sprayed by a cloud of synthetic grape juice—harmless for other desert dwellers but like pepper spray for a raven. In the lab, we watched videos of techno-torts spraying and ravens fleeing. Hardshell has weaponized juvenile tortoise models.

Other tools in the avian-management arsenal are raven-repelling lasers and drones that spray oil on raven eggs, preventing them from hatching. After repeated oilings, ravens abandon nesting sites near tortoise hot spots. On the road with Shields, we did a drive-by laser shooting of ravens roosting at a dairy, scattering hundreds in an instant. The birds' ultrasensitive vision means they respond to lasers that human eyes can barely detect; follow-up studies have revealed no damage to their sight. Stationary lasers at high-density locales have the potential to disrupt large gatherings of ravens. But who would operate them? "Agriculture, waste management, utilities—anyone can be an ally in preserving desert tortoises," Shields said.

Add gamers to the list of potential allies. Using portable, solar-powered internet nodes, Hardshell is enabling remote operation of its technology, making it potentially available to anyone with internet access, anywhere in the world. Unlike most online games, where players enter an alternate world, such games would open up the natural world. "We are a screen-based culture at this point. People view the world through screens," Shields said. "So how do we use those screens to recruit future environmentalists, particularly young people? We can bring people back to their planet through games."

Besides helping to protect the Mojave desert tortoise, Hardshell's games would offer players a chance to be heroes in real life. "I've talked to gamers about this, and their eyes light up," Shields said. "They know their game spaces are artificial constructs. They use games to escape from their world. Our games will be a reintroduction to the world, a chance to experience the joy and wonder of wild nature and help save endangered species without leaving their homes."

That joy, Shields believes, is the key to expanding the environmental movement. "If you look at any group of humans, once they achieve basic material security, they start playing games, making music, sitting around and telling stories. We pursue joy. It's universal." He paused. "We have to figure out how to make environmental action joyful."

By Leonie Sherman

March 19, 2023

There was a dead tortoise in my car. She had survived 50 years in the Mojave Desert, the hottest and driest desert in North America, growing from a two-inch hatchling to a fully armored 12-pound beast on a diet of tiny wildflowers, cacti, and dried plants. She and her ancestors had roamed this land for 15 million years, but California's historic drought likely killed her. Tortoise conservationist Tim Shields and I were bringing her carcass to a makerspace in Barstow. There, his company, Hardshell Labs, could create a 3D-printed model of her—a "techno-tort"—that could be used in experimental tortoise conservation.

Along with drought, ravens are a major threat to desert tortoises, having learned that juveniles make a tasty snack (their shells don't fully harden for five to eight years). Though ravens are native to the Mojave Desert, their numbers have exploded as they have followed humans into this inhospitable terrain. "Look at this place from the point of view of a raven," Shields said, gesturing toward the scattered homes and crumbling shacks in the scrubby desert outside Joshua Tree National Park as we drove by. "Ravens in the numbers we're seeing would not hack it out here without humans. The only water in many of these valleys is from humans. They know they can get a drink and some shade at each of these structures. I've seen a couple of roadkills just this morning; each one creates a reliable cafeteria for them." He shook his head and sighed. "Ravens are ecological vacuum cleaners. We've imported mobile, highly motivated, highly intelligent, adaptable predators into prime desert tortoise habitat. It's an eco-systemic disaster."

Since Shields began studying these tortoises in 1978, their numbers have declined by 95 percent. One time, a biologist found 136 tortoise corpses under a single raven nest. Once distributed widely through the desert, tortoises now cling to isolated spots in scattered, remote locations. Raven numbers, by contrast, have increased by at least 1,500 percent in the past 40 years. Flocks in the hundreds gather where food, water, and shade are plentiful.

Shields believes that managing ecosystems is now a human obligation. "I sympathize with the sentiment that when humans start messing around with stuff, we screw it up," Shields said. "But I've put hundreds and hundreds of raven-killed baby tortoises into plastic bags. Ravens could wipe tortoises right off the planet and not skip a beat. If we don't do something, if we don't intervene, we will lose the desert tortoise over most of its range. 'Letting nature take its course' means sharing a planet with only domesticated animals and species that that can live off our subsidies."

So Hardshell Labs has pioneered the field of nonlethal avian management, disrupting raven roosting sites and protecting isolated desert tortoise habitat. For example, technicians will station a techno-tort in prime habitat on top of a hidden cylinder. When hungry corvids approach and start pecking at the "shell," they're sprayed by a cloud of synthetic grape juice—harmless for other desert dwellers but like pepper spray for a raven. In the lab, we watched videos of techno-torts spraying and ravens fleeing. Hardshell has weaponized juvenile tortoise models.

Other tools in the avian-management arsenal are raven-repelling lasers and drones that spray oil on raven eggs, preventing them from hatching. After repeated oilings, ravens abandon nesting sites near tortoise hot spots. On the road with Shields, we did a drive-by laser shooting of ravens roosting at a dairy, scattering hundreds in an instant. The birds' ultrasensitive vision means they respond to lasers that human eyes can barely detect; follow-up studies have revealed no damage to their sight. Stationary lasers at high-density locales have the potential to disrupt large gatherings of ravens. But who would operate them? "Agriculture, waste management, utilities—anyone can be an ally in preserving desert tortoises," Shields said.

Add gamers to the list of potential allies. Using portable, solar-powered internet nodes, Hardshell is enabling remote operation of its technology, making it potentially available to anyone with internet access, anywhere in the world. Unlike most online games, where players enter an alternate world, such games would open up the natural world. "We are a screen-based culture at this point. People view the world through screens," Shields said. "So how do we use those screens to recruit future environmentalists, particularly young people? We can bring people back to their planet through games."

Besides helping to protect the Mojave desert tortoise, Hardshell's games would offer players a chance to be heroes in real life. "I've talked to gamers about this, and their eyes light up," Shields said. "They know their game spaces are artificial constructs. They use games to escape from their world. Our games will be a reintroduction to the world, a chance to experience the joy and wonder of wild nature and help save endangered species without leaving their homes."

That joy, Shields believes, is the key to expanding the environmental movement. "If you look at any group of humans, once they achieve basic material security, they start playing games, making music, sitting around and telling stories. We pursue joy. It's universal." He paused. "We have to figure out how to make environmental action joyful."

| |||||||

| page_8-9.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1559 kb |

| File Type: | |

| page_14.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1121 kb |

| File Type: | |

Scientists Use 3D-Printed Shells to Ward Off Ravens and Aim to Save Desert Tortoises

In a video captured last year in Victorville, a raven can be seen pecking at a shell on the desert floor. With scrub brush and electric transmission towers in the background, three other ravens stand nearby and watch with curiosity. Without warning the shell hisses, emitting a spray that sends the birds flying.

Did the desert tortoise learn a new defense mechanism to fend off one of its biggest predators? Not quite.

But one company is hoping their invention will make ravens think twice before daring to mess with what they think is a defenseless reptile.

The booby-trapped shell was a Techno-tortoise, a 3D-printed model designed to look like a baby desert tortoise that was developed by Hardshell Labs, a company founded by Tim Shields. Shields, a wildlife biologist with more than 35 years experience, said he was inspired to start his company eight years ago after seeing firsthand the decline of the slow-moving species.

Though the desert tortoise in the Mojave has been protected as a federally threatened species since 1990, scientists found in 2014 their numbers in the western Mojave Desert had dropped roughly 50% from those counted 10 years earlier.

Other studies estimate tortoise populations have collapsed as much as 90% since the 1980s. As a contract field biologist for the Bureau of Land Management, Shields would spend upwards of three months living and studying in desert tortoise habitat, never seeing another human being. In the early days, he’d see plenty of tortoises. That pattern changed as the years progressed.

“More and more, the track of my career has been from going from days that were absolutely packed with interactions with tortoises to now, a tortoise encounter being a rare event,” he said in a 2015 video.

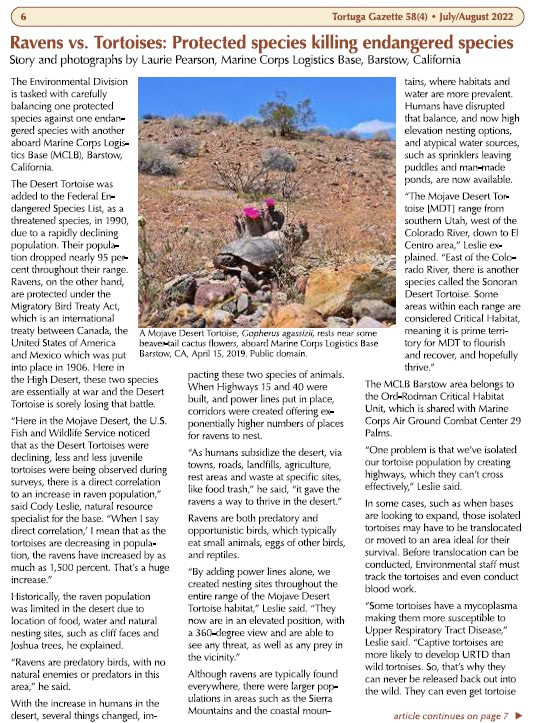

Killer ravens

Scientists note several factors as contributing to the decline: Urban development destroying tortoise habitat, invasive plant species, disease, off-road racing and vehicle strikes. For Shields, one factor stuck out above the rest as potentially solvable. “There’s a lot of threats to tortoises, but raven predation seemed to be the one we could do something about,” he said in an interview Friday.

In contrast to the tortoises, common ravens flourish in the west. Once an uncommon bird to see in the western Mojave Desert, populations of the black bird rose 795% from 1968 to 2014, according to the Breeding Bird Survey.

Increased human presence in the region drove this explosion. With more people living in the desert, ravens can scavenge trash and roadkill, nest on electrical towers and dip their beaks in man-made sources of water.

They also use their beaks to poke holes and kill young tortoises. The reptiles are essentially defenseless to the attacks during the first decade or more of their lives because their shells aren’t as strong.

Scientists have found kill sites with dozens to hundreds of shells scattered beneath raven nests.

To save his beloved creatures, Shields said he had to switch from being a tortoise biologist to a raven biologist.

Since its inception in 2014, the main focus of Hardshell Labs is to invent technologies to prevent damage from birds.

Shields’ team developed a system of using drones to oil raven eggs in nests that could be 20 to 100 feet off the ground. The oil prevents the eggs from hatching while the raven parents remain unaware and continue nesting.

The first models of the Techno-tortoise, on the other hand, started off as just a simple lure to attract the birds.

Inspired by Styrofoam tortoise models in the 1990s created by Bill Boarman, Hardshell’s lead scientist, Shields and his colleagues collaborated with the software company Autodesk to create something more lifelike using 3D-printing. The initial decoy shells were used to calculate and understand the threat of ravens by measuring the rate of attacks.

Hardshell Labs deployed a wide spread of the rubes in 2018 and 2019 and sold about 1,000 to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fast Company reported. Later models were installed with sensors that would trigger a blast of bird repellent when fiddled with.

Five counter attacking shells were placed in the field along with cameras for the first time in spring 2021. One spot the Hardshell team picked was a popular roost in northern Victorville where Shields said 6,500 ravens have been recorded. The results were exciting. Footage from one test showed an innocuous-looking shell scaring an aptly-named treachery, or group, of at least more than a dozen ravens into the air.

“So we know the device works. It does the first thing it needs to do which is scare the bejesus out of ravens,” Shields said. “Now we have to figure out, OK, if you get that effect does that reduce raven predation on tortoises. That’s a much harder question to answer.”

The biologist and others who use the shells hope the birds — which are considered one of the most intelligent animals on Earth — will learn and teach their brood to stay away from tortoises. Shields said he plans to test another 10 spraying shells in the field this year. In the meantime, plans are being proposed to make the Techno-tortoise robotically mobile to even better deceive the ravens and keep them guessing. It's all an effort to save a reptile that Shields said he has an endearment toward.

“Tortoises just gave me a great life and I just want to keep them on the planet,” he said. “Earth would be a lot more boring without tortoises.”

Did the desert tortoise learn a new defense mechanism to fend off one of its biggest predators? Not quite.

But one company is hoping their invention will make ravens think twice before daring to mess with what they think is a defenseless reptile.

The booby-trapped shell was a Techno-tortoise, a 3D-printed model designed to look like a baby desert tortoise that was developed by Hardshell Labs, a company founded by Tim Shields. Shields, a wildlife biologist with more than 35 years experience, said he was inspired to start his company eight years ago after seeing firsthand the decline of the slow-moving species.

Though the desert tortoise in the Mojave has been protected as a federally threatened species since 1990, scientists found in 2014 their numbers in the western Mojave Desert had dropped roughly 50% from those counted 10 years earlier.

Other studies estimate tortoise populations have collapsed as much as 90% since the 1980s. As a contract field biologist for the Bureau of Land Management, Shields would spend upwards of three months living and studying in desert tortoise habitat, never seeing another human being. In the early days, he’d see plenty of tortoises. That pattern changed as the years progressed.

“More and more, the track of my career has been from going from days that were absolutely packed with interactions with tortoises to now, a tortoise encounter being a rare event,” he said in a 2015 video.

Killer ravens

Scientists note several factors as contributing to the decline: Urban development destroying tortoise habitat, invasive plant species, disease, off-road racing and vehicle strikes. For Shields, one factor stuck out above the rest as potentially solvable. “There’s a lot of threats to tortoises, but raven predation seemed to be the one we could do something about,” he said in an interview Friday.

In contrast to the tortoises, common ravens flourish in the west. Once an uncommon bird to see in the western Mojave Desert, populations of the black bird rose 795% from 1968 to 2014, according to the Breeding Bird Survey.

Increased human presence in the region drove this explosion. With more people living in the desert, ravens can scavenge trash and roadkill, nest on electrical towers and dip their beaks in man-made sources of water.

They also use their beaks to poke holes and kill young tortoises. The reptiles are essentially defenseless to the attacks during the first decade or more of their lives because their shells aren’t as strong.

Scientists have found kill sites with dozens to hundreds of shells scattered beneath raven nests.

To save his beloved creatures, Shields said he had to switch from being a tortoise biologist to a raven biologist.

Since its inception in 2014, the main focus of Hardshell Labs is to invent technologies to prevent damage from birds.

Shields’ team developed a system of using drones to oil raven eggs in nests that could be 20 to 100 feet off the ground. The oil prevents the eggs from hatching while the raven parents remain unaware and continue nesting.

The first models of the Techno-tortoise, on the other hand, started off as just a simple lure to attract the birds.

Inspired by Styrofoam tortoise models in the 1990s created by Bill Boarman, Hardshell’s lead scientist, Shields and his colleagues collaborated with the software company Autodesk to create something more lifelike using 3D-printing. The initial decoy shells were used to calculate and understand the threat of ravens by measuring the rate of attacks.

Hardshell Labs deployed a wide spread of the rubes in 2018 and 2019 and sold about 1,000 to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fast Company reported. Later models were installed with sensors that would trigger a blast of bird repellent when fiddled with.

Five counter attacking shells were placed in the field along with cameras for the first time in spring 2021. One spot the Hardshell team picked was a popular roost in northern Victorville where Shields said 6,500 ravens have been recorded. The results were exciting. Footage from one test showed an innocuous-looking shell scaring an aptly-named treachery, or group, of at least more than a dozen ravens into the air.

“So we know the device works. It does the first thing it needs to do which is scare the bejesus out of ravens,” Shields said. “Now we have to figure out, OK, if you get that effect does that reduce raven predation on tortoises. That’s a much harder question to answer.”

The biologist and others who use the shells hope the birds — which are considered one of the most intelligent animals on Earth — will learn and teach their brood to stay away from tortoises. Shields said he plans to test another 10 spraying shells in the field this year. In the meantime, plans are being proposed to make the Techno-tortoise robotically mobile to even better deceive the ravens and keep them guessing. It's all an effort to save a reptile that Shields said he has an endearment toward.

“Tortoises just gave me a great life and I just want to keep them on the planet,” he said. “Earth would be a lot more boring without tortoises.”

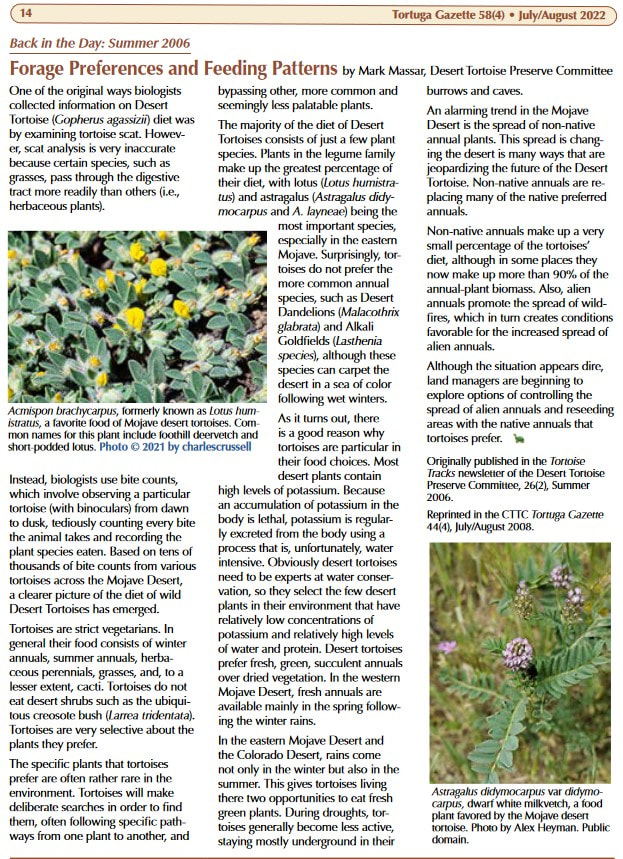

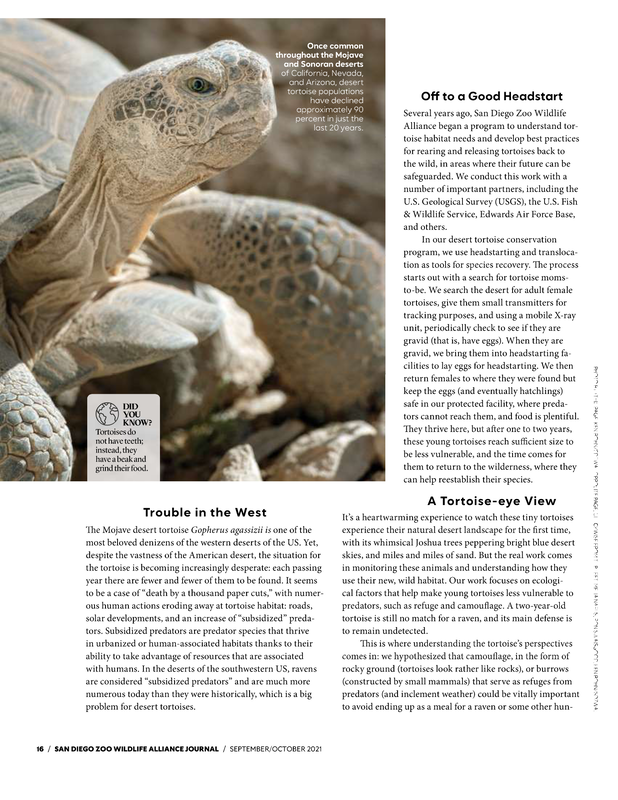

Consider this:You are only about an inch high and very slow moving. You do have a hard outer shell, which is helpful at keeping some predators from eating you. Still, many predators think of you as a crunchy-on-the-outside, juicy-on-the-inside treat. What's more, you live in a harsh desert environment, and are fortunate if you get a few drinks of water each year. You may have guessed by now that you are a desert tortoise. Getting "inside a tortoise's shell" to understand its perspective on the world is a large part of what we do to try to better conserve this species.

By Ron Swaisgood, Ph.D., Melissa Merrick, Ph.D., and /Tali Hammond, Ph.D. |

Desert Tortoise Upgraded to Critically Endangered on IUCN Red List

The IUCN Red List upgraded the desert tortoise to critically endangered. To see this, go to the IUCN Red list website: (https://www.iucnredlist.org) and type in Gopherus agassizii. View the report below.

https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:1f5c6856-7cec-4b16-818f-5f51c5b56d28

https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:1f5c6856-7cec-4b16-818f-5f51c5b56d28

The Heat is On: Desert Tortoises and Survival

|

|

|

I am pleased to report to our supporters that I signed the petition described in the following article, last March, in my capacity as President of The Desert Tortoise Preserve Committee, joining our friends at Defenders of Wildlife as well as at The Desert Tortoise Council, which we submitted to the California Fish and Game Commission.

|

Frequent Wildfires

|

Coat the Ravens Evermore?To protect tortoises, officials test spraying oil onto bird's eggs.

|

Turtles and Tortoises

|

To Save Desert Tortoises, Make Conservation

|

The Common Raven Boom in the Rugged West Isn't Necessarily a Good Thing.The raven population has ballooned over past decades, upsetting ecosystems and endangering wildlife. To check the ravenous birds, conservationists are cleaning up trash and shooting lasers...

|

Tortoise in Peril.Desert tortoises are a threatened species. Habitat destruction, diseases and other factors have reduced their numbers by up to 90 percent.

|

The Desert's Canary: A Narrative Examination

|

Pacific Southwest Region External Affairs

|

The tortoise and the desertThe desert tortoise, the state reptile for California and Nevada, likes to spend its time burrowing in holes near mountain slopes. In the summer months, temperatures can easily reach a blistering 120°F in the Mojave Desert. Seeking shelter from the heat, tortoises burrow in the ground or seek refuge in the shade of shrubs. In the winter, temperatures can reach below freezing, and tortoises snuggle into burrows once again to stay warm and conserve energy when less food is available. Other species also rely upon the desert tortoise and its burrowing skills for shelter to escape the harsh climate.

In the spring and fall, desert tortoises can be found roaming the 25,000-square-mile Mojave Desert, looking for mates and the food and water needed for survival. Native forbs that only sprout during a narrow window in the spring provide most of their food. They rely on water stored in their bladders to prevent dehydration. This water storage allows them to go without a drink for a year. Finally, the tortoise’s exterior shell offers protection from predators. Adaptations like these allow desert tortoises to live up to 70 years in the wild. So, why has the population in the Mojave Desert dropped 90 percent in some areas since the 1980s? |

Threats to the desert tortoiseDesert tortoises are dying at alarming rates, primarily due to invasive species of grass, especially red brome and cheatgrass (Bromus rubens and Bromus tectorum). Foreign to the Mojave Desert, these grasses are not as nutritious to tortoises as their normal forage.

“The red brome in particular has these very spiky awns on the seedheads and those get lodged inside the tortoises’ mouths,” says Roy Averill-Murray, desert tortoise recovery coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “The tortoises will eat them especially if they don't have a lot of other choices. [Their mouths] could become infected and then they can have difficulty eating anything else and it could cause severe health issues.” Research by U.S. Geological Survey scientists showed that juvenile tortoises that had to rely on red brome as forage grew less and declined in health compared to juveniles that had native plants to eat. |

|

To make matters worse, the invasive grass dries quickly as spring temperatures warm and the grass forms dense undergrowth that burns easily by lightning strikes or cigarette embers. Many tortoises caught on the surface during a fire are killed, while those in burrows also may succumb to smoke inhalation. Wildfires are increasing in the Mojave Desert over the past two decades as a result of the invasion. More than 400,000 acres of tortoise habitat burned in 2005 alone.

|