Check out this great video:

Desert Tortoise - for Desert Tortoise Symposium

Can we save Mojave desert tortoises by moving them out of harm’s way?Story by Emily Green/High Country News

Kristin Berry's khaki hat flaps in the wind as she bends to inspect the skeleton of a desert tortoise. Remnants of its head and neck are still attached to the carapace, and bleached bones protrude from it. It's been dead for about four years, she suspects, and "appears to have died in a relaxed position," she says, "with its legs out." That suggests starvation and dehydration, but the 70-year-old biologist can't be sure. |

It's the second week of April, when wild tortoises typically emerge from hibernation to forage on the spring wildflowers that briefly brighten the Mojave Desert. Berry –– who does long-term research on the desert tortoise for the U.S. Geological Survey –– is the acknowledged authority on where the now-threatened reptiles once thrived.

The rock outcropping where she stands is not far from I-15, halfway between L.A. and Las Vegas. Basalt hills rise to the north and west, and a cavalcade of power lines runs south. To the east, ORV tracks surround a makeshift bull's-eye riddled with bullet holes and what remains of a desert tortoise burrow. An empty Coors can is lodged in the burrow's entrance.

The ex-tortoise next to Berry wasn't hatched here. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service moved it and about 600 others 40 miles from their native range near Barstow, Calif., when the Army's Fort Irwin was expanded in 2008. Berry has been tracking it, and 157 other displaced tortoises. So far, perhaps half of the relocated animals are still alive. Nobody knows if that is good, bad or typical, or if the decline will continue. Berry's study will pit her carefully accrued survival data against the increasingly popular idea that desert tortoises can be protected, not by diverting development, but by moving animals.

This process is called "translocation." Since the desert tortoise came under Endangered Species Act protection in 1989, translocation has become the default solution to conflicts between people and tortoises. Thousands of tortoises have been moved to make way for modern Las Vegas, and for other desert development projects. Now, thousands more may be dug up to fast-track industrial-scale solar and wind farms throughout the Mojave. "It's an incredibly depressing, sad story," says Defenders of Wildlife lawyer Mike Senatore. "I think the approach is basically, 'We can't say no to anything. We have to allow renewable energy projects to go where they shouldn't go. We have to allow off-road vehicles. We have to allow military expansion and housing. So we either pave over tortoises that are there, or we go out and pick up the ones we can find.' "

Increasingly, the Fish and Wildlife Service acknowledges that it's moving a lot of turtles and needs to do more to ensure they survive. The agency's Desert Tortoise Recovery Office coordinator, a 45-year-old biologist out of Arizona named Roy Averill-Murray, and his supporters believe translocation can become a pillar of conservation, not just as a way to protect tortoises from development, but also as a way to boost populations. A long history of disturbances, from grazing to off-road vehicles to invasive plants, is steadily extirpating the species, even in places that haven't been swallowed by housing or other projects.

Berry is well aware of the translocation push -- and dismayed by it. Her research helped inspire the reptile's original Endangered Species Act listing, and she wrote much of a now-discarded 1994 recovery plan that emphasized preserving habitat and considered moving the animals a tool of last resort, noting that it may prove useful "once translocation techniques have been perfected."

In 2004, the Fish and Wildlife Service brought in Averill-Murray and a new team to rewrite the 1994 plan. The revised plan, released in 2011, sees translocation as central to recovery, pointing out that recent efforts have been more successful than earlier attempts. No longer are animals just dropped in the desert; researchers often put up temporary fencing to keep tortoises from going back home, and dig new dens with the same orientation as the old ones –– even sprinkling them with sand and feces from their former homes.

The 2011 plan also requires the creation of new guidelines and protocols for translocation. Averill-Murray is now working with biologists from the San Diego Zoo to improve the handling and resettlement of animals displaced by development. The agency also plans to start repopulating public land near Las Vegas, using unwanted pets dropped off at a facility originally meant to house displaced wild tortoises.

But Berry remains skeptical. There are too many unanswered questions, she says. Will local population genetics get muddied? What about the animals' strong homing instincts and the impacts on resident tortoises? Last year, Berry and other independent scientists prepared a report for the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, a state and federal plan to develop solar power while protecting wildlife. It concluded: "In general, moving organisms from one area to another ... is not a successful conservation action and may do more harm than good to conserved populations by spreading diseases … increasing mortality, and decreasing reproduction and genetic diversity."

Scientists generally agree that translocation has negative consequences for wildlife, especially animals as intimately tied to their homes as tortoises. "They know where every little water catchment is," says Brian K. Sullivan, an Arizona State University professor who specializes in herpetology. "They'll travel hundreds of meters to reach them when it rains. And they have strong social structures. No wonder they're traumatized when we wrench them out of their landscape and drop them somewhere else."

Before translocation, before Fort Irwin, before Westward expansion, before the Mojave was even a desert, tortoises browsed the West. The desert tortoise's ancestry goes back about 19 million years. Fossils have been found in White Pine County, Nev., more than 100 miles from the species' present range. Tortoises once roamed California's Orange County and Central Valley. Their genes carry adaptations to the tremendous changes that turned woodlands to grassland, then grassland to desert succulents and creosote scrub. Today, they're found in portions of the Mojave and Sonoran deserts in California, Nevada, Utah and Arizona.

Unlike their gigantic, lumbering Galapagos Islands cousins, desert tortoises are high-domed, light-stepping, almost jaunty little animals, 15 inches long on average. They browse on cactus, wildflowers and grasses, and their stout front legs make them excellent diggers of dens. They play a keystone role in the ecosystem: Their burrows shelter other species and they stir up and aerate the soil and disperse plant seeds. Long necks, handsome faces and curious gazes have helped earn them "state reptile" status in both California and Nevada.

They are one of the most studied turtles in the United States. But it was not always thus. Back in the 1860s, a scientist plucked a specimen from the desert, pickled it in formaldehyde and named it Gopherus agassizii –– "Gopherus" after gophers and "agassizii" in honor of Swiss paleontologist Louis Agassiz. It took another 70 years before two Utah scientists started wondering how the animals survived in such extreme conditions.

Angus Woodbury and Ross Hardy monitored a colony near St. George, Utah, from 1930 to 1947, studying how tortoise shells harden, noting how few hatchlings escape the jaws of foxes and coyotes, observing that some tortoises were gregarious while others were shy. Tortoises, they saw, had an excellent sense of color and might mistake pink clothing for edible flowers. They can go for a year or more without water because half their weight is stored in their bladders; if you disturb one, it might release all that liquid on you, then die from dehydration. Perhaps most intriguing, they concluded that most of the tortoise's energy didn't go to sex or foraging. Instead, it went to negotiating Mojave temperature swings between zero and 130 degrees Fahrenheit -- digging deep dens to escape freezing, finding shade to cool off. And the animals were attached to those dens; when carried out of their home range, they made frantic beelines back.

After Woodbury and Hardy, a quarter century passed before another researcher applied the same kind of dedication to studying Gopherus agassizii. But rather than focus on a single colony, Berry studied dozens in a sweeping effort to define its range in the western Mojave Desert.

"Intelligent … serious … formal": These are some of the words that a member of her University of California, Berkeley thesis committee used to describe Kristin Berry in 1971. Meet her once and you start choosing your words carefully. She listens so intently and answers questions with such clarity that an encounter with her is like wandering into a spotlight. Steve Schwarzbach, Berry's supervisor at the USGS, remembers when she met a photography crew in Ridgecrest, Calif., in May 2000 to lead a tour. As she was crossing a street, the perhaps 5-foot-3-inch, 110-pound scientist was struck by a car.

"Not a small car, something like an Impala," says the director of the Western Ecological Research Center in Sacramento. "She was hit so hard that she was thrown from a pedestrian crossing. But she led the tour before getting treatment," despite injuries severe enough to later require two back surgeries.

The daughter of a physicist at the China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station, Berry grew up north of Los Angeles, out where the Mojave Desert meets the Sierra. So many wildflowers bloomed after winter and early spring rains that tortoises browsed until their beaks ran green. "I once saw eight in one place," says Berry, recalling how common the reptiles were.

She was preparing a doctoral dissertation at UC Berkeley on the chuckwalla lizard, a stocky Southwestern cousin of the iguana, when she became a teaching assistant for Robert Stebbins, author of the Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. Her thesis committee included Starker Leopold, son of legendary ecologist Aldo Leopold, and David Wake, then director of herpetology at Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Biology. "Bob was not typically very close with his students," says Wake. "Kristin was an exception. I think Bob saw in Kristin someone really dedicated to conservation."

In 1971, her dissertation delivered, Berry received a call from the California Department of Transportation, which was widening Highway 58 through tortoise habitat. She knew about herbivorous reptiles, right? "They had already marshaled the Boy Scouts and they were going to dump the tortoises on China Lake," she says. "They released them in July, which was the worst possible time. We had to pull the ones we could find, because they couldn't dig a burrow fast enough to get out of the heat and were foaming at the mouth." She realized then, she says, "Nobody had any idea what they were doing with translocation."

The experience intensified her creeping sense that tortoises were becoming scarcer. Berry joined fellow desert lovers in badgering the Bureau of Land Management to designate a safe haven for the animals on roughly 40 square miles between China Lake and Edwards Air Force Base. Stebbins and Leopold were enlisted as heavyweight names in their letter-writing campaign. Once the BLM agreed in 1973 to the creation of what became the Desert Tortoise Natural Area, Berry says a staffer wearily asked her, "Would you get your friends to stop writing now?"

The following year, the BLM's California Desert District Office hired its pesterer. The dainty, exacting Berry was one of the first women to infiltrate the cowboy culture of field offices. She piled boxes on the extra chair in her office so colleagues wouldn't plop down and socialize while she was working. In one of her first projects, she helped draft multiple-use plans for California's roughly 22-million-acre chunk of the Mojave.

Berry knew that the tortoise was threatened by an ever-expanding network of military bases, with a collective footprint already larger than the state of Connecticut, as well as by more than 30,000 miles of transmission lines, pipeline and roads. But setting aside land for tortoises required understanding exactly where they lived. "We didn't know about their distribution," she says.

She began organizing dozens of long-term study plots, where researchers walked mile after mile in search of burrow entrances underneath ancient creosote. Tortoises were periodically caught, marked and recaptured. Elsewhere, she laid out more than 1,500 transects, and over the years, Berry and more than 100 young fieldworkers she's trained have repeatedly patrolled them, looking for live animals, carcasses, scat and burrows. "I was thinking ahead," she says, collecting long-term evidence.

In 1980, a stunning update came from state biologists in Utah: The Beaver Dam Slope colony Woodbury and Hardy once studied had crashed, from 300 to just 82 animals. In response, the population was listed as "threatened" under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Four years later, Berry published an 848-page report showing Mojave-wide declines that made Beaver Dam Slope look mild. The population had dropped as much as 90 percent in the last century, from historic densities of perhaps 150 tortoises per square kilometer. It was less a question of "whodunit" than "what hadn't." Cattle competed for grass and spread invasive weeds. Dune buggies and motorbikes destroyed forage and entombed tortoises in their own burrows. Highways divided historic territories, and some people used tortoises for target practice. In drought years, coyotes devoured them, and the ravens that followed humans and landfills into the desert ate the soft-shelled young and eviscerated adults.

The animals were disappearing faster than they could reproduce. Like humans, tortoises can live 50 to 80 years and don't procreate until their teens. But only about 2 percent of their offspring survive to maturity in the wild. Defenders of Wildlife, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Environmental Defense Fund petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the entire Mojave population. The agency agreed that listing was warranted but said other, higher priorities precluded it.

In 1988, a graduate student working at the Desert Tortoise Natural Area noticed that many of the animals were sick and dying. "They appeared to be dehydrated with sunken eyes," Berry says. "They had dried snot on their front legs where they would rub their nose and eyes. Some were emaciated and limp and had muscle wasting."

Berry's team surveyed the site and found staggering losses: More than 600 carcasses, and 43 percent of the living animals showed symptoms. Again, environmental groups petitioned Fish and Wildlife to list the entire Mojave desert tortoise population. This time it responded, issuing an emergency "endangered" order in 1989.

Pathologists were flown in to euthanize and autopsy sick tortoises, and reports of illness in other colonies came in. They discovered that the reptiles were afflicted by an upper respiratory tract disease caused by a novel strain of Mycoplasma, the bacteria associated with human "walking pneumonia." Outbreaks in wild populations near cities convinced Berry and others that it had been introduced by the surreptitious dumping of sick pet tortoises.

But the disease hit Kern County hardest; the tortoise was not at risk of extinction throughout the rest of its range. So, in 1990, its status was reduced to "threatened."

Berry became one of the chief contributors to a recovery plan striving for the highest possible conservation values, and 6.4 million acres of critical habitat were designated. The plan divided tortoises into six evolutionarily distinct groups in a way that anticipated by almost 20 years their eventual splitting into two species -- Gopherus agassizii to the west of the Colorado River, and the Sonoran's more hill-dwelling Gopherus morafkai to the east. Recovery efforts for each group would be tailored to local conditions. Though the 1994 plan was widely applauded by environmentalists, it was promptly lost in bureaucratic red tape.

When, a decade later, Fish and Wildlife hired Averill-Murray to rewrite it, Berry was left out of his team's inner circle. She had moved to the U.S. Geological Survey in 1993, but continued her tortoise work. Not only did she distrust translocation in general, she was also convinced that translocating captive tortoises could seed new epidemics like the one that sparked the listing in the first place.

But development was exploding in the southern Nevada desert, and Averill-Murray's team had only two options. A study in The Journal of Wildlife Management sums up the dilemma they faced: "The conservation of habitat should always take precedence for conservation planning, but when habitat is lost because of political or economical decisions, only 2 choices remain: 1) leave animals in harm's way to die … or 2) collect the animals assuming that they may be useful for conservation in the future."

Averill-Murray chose Door #2. Tortoises were not stopping the industrialization of the Mojave, so his team created a plan that would concentrate management under a Reno-based office that would lead translocation efforts, and adjust recovery actions based on changing climate and other factors.

To increase the survival rate for translocated tortoises, his group wanted to experiment with captive animals. Although 3,000 had been euthanized at a holding facility because they'd been exposed to Mycoplasma, his group was increasingly convinced that the disease was not chronic, like tuberculosis, but rather more like a passing cold. As they saw it, there was no time to waste in the increasingly desperate quest to improve translocation protocols.

The rock outcropping where she stands is not far from I-15, halfway between L.A. and Las Vegas. Basalt hills rise to the north and west, and a cavalcade of power lines runs south. To the east, ORV tracks surround a makeshift bull's-eye riddled with bullet holes and what remains of a desert tortoise burrow. An empty Coors can is lodged in the burrow's entrance.

The ex-tortoise next to Berry wasn't hatched here. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service moved it and about 600 others 40 miles from their native range near Barstow, Calif., when the Army's Fort Irwin was expanded in 2008. Berry has been tracking it, and 157 other displaced tortoises. So far, perhaps half of the relocated animals are still alive. Nobody knows if that is good, bad or typical, or if the decline will continue. Berry's study will pit her carefully accrued survival data against the increasingly popular idea that desert tortoises can be protected, not by diverting development, but by moving animals.

This process is called "translocation." Since the desert tortoise came under Endangered Species Act protection in 1989, translocation has become the default solution to conflicts between people and tortoises. Thousands of tortoises have been moved to make way for modern Las Vegas, and for other desert development projects. Now, thousands more may be dug up to fast-track industrial-scale solar and wind farms throughout the Mojave. "It's an incredibly depressing, sad story," says Defenders of Wildlife lawyer Mike Senatore. "I think the approach is basically, 'We can't say no to anything. We have to allow renewable energy projects to go where they shouldn't go. We have to allow off-road vehicles. We have to allow military expansion and housing. So we either pave over tortoises that are there, or we go out and pick up the ones we can find.' "

Increasingly, the Fish and Wildlife Service acknowledges that it's moving a lot of turtles and needs to do more to ensure they survive. The agency's Desert Tortoise Recovery Office coordinator, a 45-year-old biologist out of Arizona named Roy Averill-Murray, and his supporters believe translocation can become a pillar of conservation, not just as a way to protect tortoises from development, but also as a way to boost populations. A long history of disturbances, from grazing to off-road vehicles to invasive plants, is steadily extirpating the species, even in places that haven't been swallowed by housing or other projects.

Berry is well aware of the translocation push -- and dismayed by it. Her research helped inspire the reptile's original Endangered Species Act listing, and she wrote much of a now-discarded 1994 recovery plan that emphasized preserving habitat and considered moving the animals a tool of last resort, noting that it may prove useful "once translocation techniques have been perfected."

In 2004, the Fish and Wildlife Service brought in Averill-Murray and a new team to rewrite the 1994 plan. The revised plan, released in 2011, sees translocation as central to recovery, pointing out that recent efforts have been more successful than earlier attempts. No longer are animals just dropped in the desert; researchers often put up temporary fencing to keep tortoises from going back home, and dig new dens with the same orientation as the old ones –– even sprinkling them with sand and feces from their former homes.

The 2011 plan also requires the creation of new guidelines and protocols for translocation. Averill-Murray is now working with biologists from the San Diego Zoo to improve the handling and resettlement of animals displaced by development. The agency also plans to start repopulating public land near Las Vegas, using unwanted pets dropped off at a facility originally meant to house displaced wild tortoises.

But Berry remains skeptical. There are too many unanswered questions, she says. Will local population genetics get muddied? What about the animals' strong homing instincts and the impacts on resident tortoises? Last year, Berry and other independent scientists prepared a report for the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, a state and federal plan to develop solar power while protecting wildlife. It concluded: "In general, moving organisms from one area to another ... is not a successful conservation action and may do more harm than good to conserved populations by spreading diseases … increasing mortality, and decreasing reproduction and genetic diversity."

Scientists generally agree that translocation has negative consequences for wildlife, especially animals as intimately tied to their homes as tortoises. "They know where every little water catchment is," says Brian K. Sullivan, an Arizona State University professor who specializes in herpetology. "They'll travel hundreds of meters to reach them when it rains. And they have strong social structures. No wonder they're traumatized when we wrench them out of their landscape and drop them somewhere else."

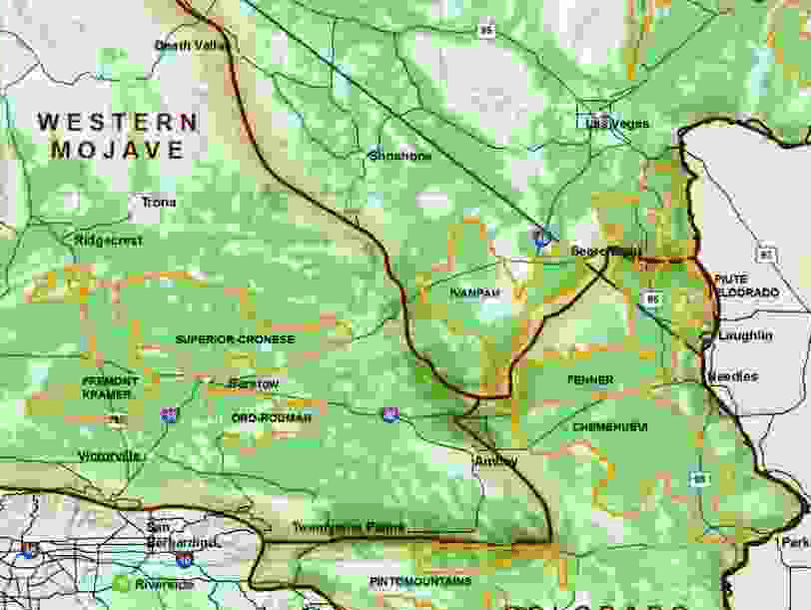

Before translocation, before Fort Irwin, before Westward expansion, before the Mojave was even a desert, tortoises browsed the West. The desert tortoise's ancestry goes back about 19 million years. Fossils have been found in White Pine County, Nev., more than 100 miles from the species' present range. Tortoises once roamed California's Orange County and Central Valley. Their genes carry adaptations to the tremendous changes that turned woodlands to grassland, then grassland to desert succulents and creosote scrub. Today, they're found in portions of the Mojave and Sonoran deserts in California, Nevada, Utah and Arizona.

Unlike their gigantic, lumbering Galapagos Islands cousins, desert tortoises are high-domed, light-stepping, almost jaunty little animals, 15 inches long on average. They browse on cactus, wildflowers and grasses, and their stout front legs make them excellent diggers of dens. They play a keystone role in the ecosystem: Their burrows shelter other species and they stir up and aerate the soil and disperse plant seeds. Long necks, handsome faces and curious gazes have helped earn them "state reptile" status in both California and Nevada.

They are one of the most studied turtles in the United States. But it was not always thus. Back in the 1860s, a scientist plucked a specimen from the desert, pickled it in formaldehyde and named it Gopherus agassizii –– "Gopherus" after gophers and "agassizii" in honor of Swiss paleontologist Louis Agassiz. It took another 70 years before two Utah scientists started wondering how the animals survived in such extreme conditions.

Angus Woodbury and Ross Hardy monitored a colony near St. George, Utah, from 1930 to 1947, studying how tortoise shells harden, noting how few hatchlings escape the jaws of foxes and coyotes, observing that some tortoises were gregarious while others were shy. Tortoises, they saw, had an excellent sense of color and might mistake pink clothing for edible flowers. They can go for a year or more without water because half their weight is stored in their bladders; if you disturb one, it might release all that liquid on you, then die from dehydration. Perhaps most intriguing, they concluded that most of the tortoise's energy didn't go to sex or foraging. Instead, it went to negotiating Mojave temperature swings between zero and 130 degrees Fahrenheit -- digging deep dens to escape freezing, finding shade to cool off. And the animals were attached to those dens; when carried out of their home range, they made frantic beelines back.

After Woodbury and Hardy, a quarter century passed before another researcher applied the same kind of dedication to studying Gopherus agassizii. But rather than focus on a single colony, Berry studied dozens in a sweeping effort to define its range in the western Mojave Desert.

"Intelligent … serious … formal": These are some of the words that a member of her University of California, Berkeley thesis committee used to describe Kristin Berry in 1971. Meet her once and you start choosing your words carefully. She listens so intently and answers questions with such clarity that an encounter with her is like wandering into a spotlight. Steve Schwarzbach, Berry's supervisor at the USGS, remembers when she met a photography crew in Ridgecrest, Calif., in May 2000 to lead a tour. As she was crossing a street, the perhaps 5-foot-3-inch, 110-pound scientist was struck by a car.

"Not a small car, something like an Impala," says the director of the Western Ecological Research Center in Sacramento. "She was hit so hard that she was thrown from a pedestrian crossing. But she led the tour before getting treatment," despite injuries severe enough to later require two back surgeries.

The daughter of a physicist at the China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station, Berry grew up north of Los Angeles, out where the Mojave Desert meets the Sierra. So many wildflowers bloomed after winter and early spring rains that tortoises browsed until their beaks ran green. "I once saw eight in one place," says Berry, recalling how common the reptiles were.

She was preparing a doctoral dissertation at UC Berkeley on the chuckwalla lizard, a stocky Southwestern cousin of the iguana, when she became a teaching assistant for Robert Stebbins, author of the Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. Her thesis committee included Starker Leopold, son of legendary ecologist Aldo Leopold, and David Wake, then director of herpetology at Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Biology. "Bob was not typically very close with his students," says Wake. "Kristin was an exception. I think Bob saw in Kristin someone really dedicated to conservation."

In 1971, her dissertation delivered, Berry received a call from the California Department of Transportation, which was widening Highway 58 through tortoise habitat. She knew about herbivorous reptiles, right? "They had already marshaled the Boy Scouts and they were going to dump the tortoises on China Lake," she says. "They released them in July, which was the worst possible time. We had to pull the ones we could find, because they couldn't dig a burrow fast enough to get out of the heat and were foaming at the mouth." She realized then, she says, "Nobody had any idea what they were doing with translocation."

The experience intensified her creeping sense that tortoises were becoming scarcer. Berry joined fellow desert lovers in badgering the Bureau of Land Management to designate a safe haven for the animals on roughly 40 square miles between China Lake and Edwards Air Force Base. Stebbins and Leopold were enlisted as heavyweight names in their letter-writing campaign. Once the BLM agreed in 1973 to the creation of what became the Desert Tortoise Natural Area, Berry says a staffer wearily asked her, "Would you get your friends to stop writing now?"

The following year, the BLM's California Desert District Office hired its pesterer. The dainty, exacting Berry was one of the first women to infiltrate the cowboy culture of field offices. She piled boxes on the extra chair in her office so colleagues wouldn't plop down and socialize while she was working. In one of her first projects, she helped draft multiple-use plans for California's roughly 22-million-acre chunk of the Mojave.

Berry knew that the tortoise was threatened by an ever-expanding network of military bases, with a collective footprint already larger than the state of Connecticut, as well as by more than 30,000 miles of transmission lines, pipeline and roads. But setting aside land for tortoises required understanding exactly where they lived. "We didn't know about their distribution," she says.

She began organizing dozens of long-term study plots, where researchers walked mile after mile in search of burrow entrances underneath ancient creosote. Tortoises were periodically caught, marked and recaptured. Elsewhere, she laid out more than 1,500 transects, and over the years, Berry and more than 100 young fieldworkers she's trained have repeatedly patrolled them, looking for live animals, carcasses, scat and burrows. "I was thinking ahead," she says, collecting long-term evidence.

In 1980, a stunning update came from state biologists in Utah: The Beaver Dam Slope colony Woodbury and Hardy once studied had crashed, from 300 to just 82 animals. In response, the population was listed as "threatened" under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Four years later, Berry published an 848-page report showing Mojave-wide declines that made Beaver Dam Slope look mild. The population had dropped as much as 90 percent in the last century, from historic densities of perhaps 150 tortoises per square kilometer. It was less a question of "whodunit" than "what hadn't." Cattle competed for grass and spread invasive weeds. Dune buggies and motorbikes destroyed forage and entombed tortoises in their own burrows. Highways divided historic territories, and some people used tortoises for target practice. In drought years, coyotes devoured them, and the ravens that followed humans and landfills into the desert ate the soft-shelled young and eviscerated adults.

The animals were disappearing faster than they could reproduce. Like humans, tortoises can live 50 to 80 years and don't procreate until their teens. But only about 2 percent of their offspring survive to maturity in the wild. Defenders of Wildlife, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Environmental Defense Fund petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the entire Mojave population. The agency agreed that listing was warranted but said other, higher priorities precluded it.

In 1988, a graduate student working at the Desert Tortoise Natural Area noticed that many of the animals were sick and dying. "They appeared to be dehydrated with sunken eyes," Berry says. "They had dried snot on their front legs where they would rub their nose and eyes. Some were emaciated and limp and had muscle wasting."

Berry's team surveyed the site and found staggering losses: More than 600 carcasses, and 43 percent of the living animals showed symptoms. Again, environmental groups petitioned Fish and Wildlife to list the entire Mojave desert tortoise population. This time it responded, issuing an emergency "endangered" order in 1989.

Pathologists were flown in to euthanize and autopsy sick tortoises, and reports of illness in other colonies came in. They discovered that the reptiles were afflicted by an upper respiratory tract disease caused by a novel strain of Mycoplasma, the bacteria associated with human "walking pneumonia." Outbreaks in wild populations near cities convinced Berry and others that it had been introduced by the surreptitious dumping of sick pet tortoises.

But the disease hit Kern County hardest; the tortoise was not at risk of extinction throughout the rest of its range. So, in 1990, its status was reduced to "threatened."

Berry became one of the chief contributors to a recovery plan striving for the highest possible conservation values, and 6.4 million acres of critical habitat were designated. The plan divided tortoises into six evolutionarily distinct groups in a way that anticipated by almost 20 years their eventual splitting into two species -- Gopherus agassizii to the west of the Colorado River, and the Sonoran's more hill-dwelling Gopherus morafkai to the east. Recovery efforts for each group would be tailored to local conditions. Though the 1994 plan was widely applauded by environmentalists, it was promptly lost in bureaucratic red tape.

When, a decade later, Fish and Wildlife hired Averill-Murray to rewrite it, Berry was left out of his team's inner circle. She had moved to the U.S. Geological Survey in 1993, but continued her tortoise work. Not only did she distrust translocation in general, she was also convinced that translocating captive tortoises could seed new epidemics like the one that sparked the listing in the first place.

But development was exploding in the southern Nevada desert, and Averill-Murray's team had only two options. A study in The Journal of Wildlife Management sums up the dilemma they faced: "The conservation of habitat should always take precedence for conservation planning, but when habitat is lost because of political or economical decisions, only 2 choices remain: 1) leave animals in harm's way to die … or 2) collect the animals assuming that they may be useful for conservation in the future."

Averill-Murray chose Door #2. Tortoises were not stopping the industrialization of the Mojave, so his team created a plan that would concentrate management under a Reno-based office that would lead translocation efforts, and adjust recovery actions based on changing climate and other factors.

To increase the survival rate for translocated tortoises, his group wanted to experiment with captive animals. Although 3,000 had been euthanized at a holding facility because they'd been exposed to Mycoplasma, his group was increasingly convinced that the disease was not chronic, like tuberculosis, but rather more like a passing cold. As they saw it, there was no time to waste in the increasingly desperate quest to improve translocation protocols.

Roy Averill-Murray resembles a thinner Kevin Costner with a less-pronounced chin, wearing sunglasses and with a tortoise embroidered on his baseball cap. The most controversial figure in desert biology, he radiates an affability that earns the deep affection of his field workers. Whenever they come in from the desert, he has a cooler of beer waiting. He did his master's thesis on the tortoise at the University of Arizona, and worked for the state's Game and Fish Department as desert tortoise coordinator before joining the federal agency. "I've been working on tortoises for 22 years," he says. "I turned 45 this year and realized it was getting to the point that it has been close to half my life."

Just as Averill-Murray started his new job, trouble erupted over a habitat conservation plan arranged in 1990 between Clark County, Nev., and federal regulators. Under that plan, developers had agreed to build and donate a 222-acre tortoise holding facility, the Desert Tortoise Conservation Center, in south Las Vegas. For every acre of tortoise habitat lost to houses, a fee would be paid toward the running of the place, which would take in displaced wild tortoises. These animals would then be translocated, donated for lab experiments or, if diseased, humanely dispatched.

From 1990 through 2005, habitat conservation plans mimicking the Vegas model were written to cover millions of acres across Nevada and California. The parcels making up the 6.4 million acres of critical habitat became ever more isolated from one another by industrialization. In 2005, a wave of military expansions and solar and wind farms began to hit the Mojave. Of many mitigation schemes stipulated by these habitat conservation plans, from covering landfills and sewage ponds to restricting off-road vehicle use, one of the most common required purchasing mitigation land for displaced tortoises.

That soon revealed more problems with translocation schemes. There just isn't that much good unoccupied desert left, for one. "The habitat is basically full," says Berry, and in places where native populations have declined, it doesn't make sense to release more tortoises until you know why the original residents died out. Also, unless a mitigation area is protected, the animals might eventually get moved again.

Back in southern Nevada, the very facility created by the original habitat conservation model was falling apart. It had looked good on paper -- until the center began filling up, not just with displaced wild tortoises, but also surrendered pets, either captured before the species was listed or the offspring of such captives. "It's ironic that it's a threatened species and that they do so well in captivity and that creates this overabundance," says Averill- Murray. "They started piling up and piling up and piling up."

Overcrowding got so bad that, starting in 1995, more than 9,000 tortoises were released on BLM land near Jean, Nev. Nobody knows how many survived. "If you go out there today, there are a lot of dead tortoises," says Averill-Murray.

In 2010, Clark County stopped funding the Desert Tortoise Conservation Center, saying it was no longer fulfilling its original purpose. Averill-Murray doesn't blame the county. "They were spending over a million per year just dealing with pet tortoises. That's funding that wasn't going to conservation or recovery," he says. Since that time, the center has struggled to survive and is scheduled to close in 2014.

By 2011, turtle-moving was making national news. The Fish and Wildlife Service gave BrightSource Energy permission to displace roughly three dozen adult tortoises for its planned 3,500-acre Ivanpah Valley solar complex on the California-Nevada border, spurred by a federal goal stating that by 2015 plans must be in place for "renewable energy projects located on the public lands with a generation capacity of at least 10,000 megawatts of electricity."

But as tortoise after tortoise was unearthed in Ivanpah Valley, it became apparent that there were many more than originally thought -- perhaps 1,000 animals, if hatchlings and juveniles were included. After an attempt in court by the Western Watersheds Project to halt construction failed, BrightSource CEO John Woolard insisted he was actually saving turtles, telling the House Oversight Committee in 2012, "We expect to return more desert tortoises to the wild than were captured on site, as we have had over 50 new hatchling tortoises born in captivity at Ivanpah in the temporary pens last fall."

Amid the emerging chaos in Ivanpah, in March 2011, biologists poured into Las Vegas for the long-awaited revision of the recovery plan. "Everyone in the environmental community felt like this is the big unveiling moment," says Ileene Anderson, the Center for Biological Diversity's desert specialist. But it turned out that the plan was missing a crucial component. "There was this roomful, 70 or 80 people there, and then they say they didn't have time to do a renewable energy chapter, so they would add that later. It was bizarre."

"When we started the revision process (in 2004) all this renewable energy wasn't on the radar," explains Averill- Murray, "so we really didn't address those issues head on … It would have taken a wholesale change at the eleventh hour." He expects the chapter on renewable energy impacts to come out of review by the end of this year.

Once it does, given the political push toward renewable energy, Fish and Wildlife is unlikely to stymie future solar or wind power projects. But some things may be changing. "To industry's credit," says Anderson, "at least the solar folks learned their lesson with Ivanpah. They're now trying to do due diligence and select places they know have fewer tortoises." Massive solar projects are even being sited on former agricultural land instead of pristine desert.

Nonetheless, just under 52,000 acres of federal land in the Southwest, much of it tortoise habitat, have been approved for solar projects, according to BLM energy liaison Ray Brady. On top of 37 renewable energy projects licensed since 2009, the BLM is considering 20 more proposals, 14 for solar and six for wind. The agency's final environmental impact statement for solar energy zones in tortoise territory in Arizona, Nevada, Utah and California, asserts that, "Despite some risk of mortality or decreased fitness of the desert tortoise, translocation is widely accepted as a useful strategy for the conservation of this species." As evidence, it repeatedly cites a 2007 paper by Averill-Murray's team that tracked just 32 translocated animals for two years, during which a fifth of the tortoises died.

Averill-Murray's team is now working with biologists from the San Diego Zoo to use the Desert Tortoise Conservation Center's 2,000 or so captive tortoises, some of which have been exposed to Mycoplasma, in translocation experiments. Averill-Murray recognizes the risk of spreading illness to wild populations, but says, "Disease is a normal fact of life. It's unrealistic to expect that there's going to be a pure wild population out there that we're somehow going to contaminate."

Since the 1971 dumping of turtles on China Lake, translocation methods have steadily improved. Animals now must be released early in the morning and in spring, when forage and water are more available. Averill-Murray's group wants to refine the process further. So they've been experimenting to see how juveniles, which are more vulnerable to predators but theoretically less bonded to a previous habitat, do in an ongoing translocation of young turtles to the Nevada Test Site. In another experiment, they're releasing tortoises in more sheltered washes instead of in open basins, which had been widely done in the past, and rather than dipping them in a hydrating bath before release, they're injecting them with saline solution.

On the last day of April, as Averill-Murray and the San Diego Zoo team prepared 32 tortoises from the Center, a young post-doc named Jen Germano used ultrasound on female translocatees to see if they were carrying eggs. They hope the released animals will produce hatchlings to repopulate Trout Canyon, a Joshua tree-studded crease in the Pahrump Valley where once-plentiful tortoises have become scarce. Researchers in a shade tent use putty to attach radio transmitters to shells for tracking. The animals are so tame that they don't withdraw into their shells when handled. That's a defense they will quickly rediscover, says Germano: "They learn pretty fast how to be tortoises again."

The day after the animals are tested for disease and tagged, Averill-Murray's team meets at dawn and loads them up: 16 outwardly healthy but Mycoplasma-positive tortoises and 16 that have tested negative. If, as he suspects, positive antibody status is nothing more than evidence of a tortoise with a well-educated immune system and the Kern County tortoises so badly hit by Mycoplasma in 1988 were uniquely vulnerable, then that frees up a lot of experimental animals for future use.

At Trout Canyon, they're removed from the straw nests in their traveling cases, injected with saline and carried to selected locations in sheltered washes. Field staffers are visibly moved as they set the captives free. "Look at you in your new home," one biologist murmurs to GT3125, a female perhaps 20 years old.

A raven circles overhead as the tortoises begin to explore their surroundings. As the scientists depart, a civilian truck carrying a bright red dune buggy waits to drive up the dirt road towards where the tortoises are tasting their first, and possibly last, wildflowers. The tortoises will be monitored for the next five years, says Averill-Murray, provided that they survive and that funds for such monitoring last.

Just as Averill-Murray started his new job, trouble erupted over a habitat conservation plan arranged in 1990 between Clark County, Nev., and federal regulators. Under that plan, developers had agreed to build and donate a 222-acre tortoise holding facility, the Desert Tortoise Conservation Center, in south Las Vegas. For every acre of tortoise habitat lost to houses, a fee would be paid toward the running of the place, which would take in displaced wild tortoises. These animals would then be translocated, donated for lab experiments or, if diseased, humanely dispatched.

From 1990 through 2005, habitat conservation plans mimicking the Vegas model were written to cover millions of acres across Nevada and California. The parcels making up the 6.4 million acres of critical habitat became ever more isolated from one another by industrialization. In 2005, a wave of military expansions and solar and wind farms began to hit the Mojave. Of many mitigation schemes stipulated by these habitat conservation plans, from covering landfills and sewage ponds to restricting off-road vehicle use, one of the most common required purchasing mitigation land for displaced tortoises.

That soon revealed more problems with translocation schemes. There just isn't that much good unoccupied desert left, for one. "The habitat is basically full," says Berry, and in places where native populations have declined, it doesn't make sense to release more tortoises until you know why the original residents died out. Also, unless a mitigation area is protected, the animals might eventually get moved again.

Back in southern Nevada, the very facility created by the original habitat conservation model was falling apart. It had looked good on paper -- until the center began filling up, not just with displaced wild tortoises, but also surrendered pets, either captured before the species was listed or the offspring of such captives. "It's ironic that it's a threatened species and that they do so well in captivity and that creates this overabundance," says Averill- Murray. "They started piling up and piling up and piling up."

Overcrowding got so bad that, starting in 1995, more than 9,000 tortoises were released on BLM land near Jean, Nev. Nobody knows how many survived. "If you go out there today, there are a lot of dead tortoises," says Averill-Murray.

In 2010, Clark County stopped funding the Desert Tortoise Conservation Center, saying it was no longer fulfilling its original purpose. Averill-Murray doesn't blame the county. "They were spending over a million per year just dealing with pet tortoises. That's funding that wasn't going to conservation or recovery," he says. Since that time, the center has struggled to survive and is scheduled to close in 2014.

By 2011, turtle-moving was making national news. The Fish and Wildlife Service gave BrightSource Energy permission to displace roughly three dozen adult tortoises for its planned 3,500-acre Ivanpah Valley solar complex on the California-Nevada border, spurred by a federal goal stating that by 2015 plans must be in place for "renewable energy projects located on the public lands with a generation capacity of at least 10,000 megawatts of electricity."

But as tortoise after tortoise was unearthed in Ivanpah Valley, it became apparent that there were many more than originally thought -- perhaps 1,000 animals, if hatchlings and juveniles were included. After an attempt in court by the Western Watersheds Project to halt construction failed, BrightSource CEO John Woolard insisted he was actually saving turtles, telling the House Oversight Committee in 2012, "We expect to return more desert tortoises to the wild than were captured on site, as we have had over 50 new hatchling tortoises born in captivity at Ivanpah in the temporary pens last fall."

Amid the emerging chaos in Ivanpah, in March 2011, biologists poured into Las Vegas for the long-awaited revision of the recovery plan. "Everyone in the environmental community felt like this is the big unveiling moment," says Ileene Anderson, the Center for Biological Diversity's desert specialist. But it turned out that the plan was missing a crucial component. "There was this roomful, 70 or 80 people there, and then they say they didn't have time to do a renewable energy chapter, so they would add that later. It was bizarre."

"When we started the revision process (in 2004) all this renewable energy wasn't on the radar," explains Averill- Murray, "so we really didn't address those issues head on … It would have taken a wholesale change at the eleventh hour." He expects the chapter on renewable energy impacts to come out of review by the end of this year.

Once it does, given the political push toward renewable energy, Fish and Wildlife is unlikely to stymie future solar or wind power projects. But some things may be changing. "To industry's credit," says Anderson, "at least the solar folks learned their lesson with Ivanpah. They're now trying to do due diligence and select places they know have fewer tortoises." Massive solar projects are even being sited on former agricultural land instead of pristine desert.

Nonetheless, just under 52,000 acres of federal land in the Southwest, much of it tortoise habitat, have been approved for solar projects, according to BLM energy liaison Ray Brady. On top of 37 renewable energy projects licensed since 2009, the BLM is considering 20 more proposals, 14 for solar and six for wind. The agency's final environmental impact statement for solar energy zones in tortoise territory in Arizona, Nevada, Utah and California, asserts that, "Despite some risk of mortality or decreased fitness of the desert tortoise, translocation is widely accepted as a useful strategy for the conservation of this species." As evidence, it repeatedly cites a 2007 paper by Averill-Murray's team that tracked just 32 translocated animals for two years, during which a fifth of the tortoises died.

Averill-Murray's team is now working with biologists from the San Diego Zoo to use the Desert Tortoise Conservation Center's 2,000 or so captive tortoises, some of which have been exposed to Mycoplasma, in translocation experiments. Averill-Murray recognizes the risk of spreading illness to wild populations, but says, "Disease is a normal fact of life. It's unrealistic to expect that there's going to be a pure wild population out there that we're somehow going to contaminate."

Since the 1971 dumping of turtles on China Lake, translocation methods have steadily improved. Animals now must be released early in the morning and in spring, when forage and water are more available. Averill-Murray's group wants to refine the process further. So they've been experimenting to see how juveniles, which are more vulnerable to predators but theoretically less bonded to a previous habitat, do in an ongoing translocation of young turtles to the Nevada Test Site. In another experiment, they're releasing tortoises in more sheltered washes instead of in open basins, which had been widely done in the past, and rather than dipping them in a hydrating bath before release, they're injecting them with saline solution.

On the last day of April, as Averill-Murray and the San Diego Zoo team prepared 32 tortoises from the Center, a young post-doc named Jen Germano used ultrasound on female translocatees to see if they were carrying eggs. They hope the released animals will produce hatchlings to repopulate Trout Canyon, a Joshua tree-studded crease in the Pahrump Valley where once-plentiful tortoises have become scarce. Researchers in a shade tent use putty to attach radio transmitters to shells for tracking. The animals are so tame that they don't withdraw into their shells when handled. That's a defense they will quickly rediscover, says Germano: "They learn pretty fast how to be tortoises again."

The day after the animals are tested for disease and tagged, Averill-Murray's team meets at dawn and loads them up: 16 outwardly healthy but Mycoplasma-positive tortoises and 16 that have tested negative. If, as he suspects, positive antibody status is nothing more than evidence of a tortoise with a well-educated immune system and the Kern County tortoises so badly hit by Mycoplasma in 1988 were uniquely vulnerable, then that frees up a lot of experimental animals for future use.

At Trout Canyon, they're removed from the straw nests in their traveling cases, injected with saline and carried to selected locations in sheltered washes. Field staffers are visibly moved as they set the captives free. "Look at you in your new home," one biologist murmurs to GT3125, a female perhaps 20 years old.

A raven circles overhead as the tortoises begin to explore their surroundings. As the scientists depart, a civilian truck carrying a bright red dune buggy waits to drive up the dirt road towards where the tortoises are tasting their first, and possibly last, wildflowers. The tortoises will be monitored for the next five years, says Averill-Murray, provided that they survive and that funds for such monitoring last.

Almost a quarter century has passed since the Mojave desert tortoise was first listed. Nineteen years have gone by since Berry co-authored a recovery plan that, if implemented, might well have succeeded by now, say conservation groups. That 1994 plan sought to return tortoise numbers to where they were before Mycoplasma hit. The new plan seems less ambitious, with a goal of reaching the numbers found in 2001, when Fish and Wildlife began its own range-wide monitoring.

Both the original and revised plans were filled with suggestions about what should be done to recover the tortoise in addition to translocation. Over the years, federal agencies have spent millions to acquire land, install protective fences, retire grazing allotments, limit off-roading, cover landfills and close trails.

Some pieces of the 6.4 million acres of BLM land designated as critical habitat in 1994 have changed jurisdiction since then, including millions of acres transferred to the National Park Service. Most critical habitat remaining under BLM management now has special protection as "areas of critical environmental concern" or "desert wildlife management areas"; in the latter, development is limited to 1 percent of the total area. The USGS and FWS are working with energy planners to retain wildlife corridors between critical habitat areas. And yet, according to a 2012 study in BioScience by Averill-Murray and others, the "effectiveness of most recovery actions is … unknown," and in many parts of its range, the tortoise continues to decline.

"If we don't get serious about taking away some of the stressors on tortoises," says Anderson of the Center for Biological Diversity, "they may go extinct. We need habitat where the highest priority is desert tortoise conservation and where we can remove the other threats." She ticks off the big national parks, none of which are really prime tortoise territory: Death Valley is too low and too hot, while Joshua Tree's most suitable habitat is too accessible to humans, and the Mojave National Preserve allows grazing. The animal's best hope, she says, can be seen at the Desert Tortoise Natural Area that Berry helped found. It's fenced off and entirely dedicated to tortoises; other uses are excluded, including off-road vehicles. "Data from there show tortoise densities much higher than in critical habitat managed by the BLM next door," she says, citing research being done by Berry and others. "(Their) study will provide a compass on how to manage for tortoises."

And Fort Irwin, perhaps, provides a "how not to" for tortoise management. Five years after the 158 healthy tortoises tagged for Berry's study were moved, she says, "84 are dead. Another 21 are missing. Six or seven of those, we're sure they're dead. We found chewed-up transmitters."

She will track the survivors through the bleak hills near Barstow to get a long-term picture of their survival rate. For such long-lived animals, five years of living after being uprooted might still end in slow starvation, or they might genuinely be re-establishing themselves. "We still don't know if translocation works," Berry says. "We need long-term studies. We need numbers."

Even if translocation techniques are improved, she firmly believes that the best thing that can be done for the desert tortoise is to leave it alone. And in the most protected areas, that might happen. But elsewhere across a 48,000-square-mile desert, it seems inevitable that tortoise-moving will continue. For Berry, every inch a product of the late-'60s ecology movement, it's intolerable to contemplate that the animal she's devoted her life to might become dependent on the kindness of rangers.

Berry continues gathering data from her plots and transects across the Mojave and part of the Sonoran deserts. By the time she retires, says her boss, Steve Schwarzbach, her life's work will appear in what he calls her "masterpiece": the longest, most extensive survey of the animal's demographics and survival rates ever done, and a mighty study of the tortoise's passage into the Anthropocene. His provisional title for it: "The 40-year decline of the desert tortoise."

Yet when Berry is asked if she gets depressed chronicling the disappearance of an animal older than recorded history, she seems surprised. Then, in her flat, matter-of-fact way, she replies, "People like myself, the best we can do is present the best possible science and be an advocate for its use. I don't allow myself to get depressed because it takes up time -- and I don't have that much left."

Award-winning reporter Emily Green is an environmental writer based in Los Angeles. She blogs about Western water at www.chanceofrain.com.

This story was funded with reader donations to the High Country News Research Fund.

© High Country News

This article originally appeared in the Aug. 5, 2013 issue of High Country News (hcn.org)

Both the original and revised plans were filled with suggestions about what should be done to recover the tortoise in addition to translocation. Over the years, federal agencies have spent millions to acquire land, install protective fences, retire grazing allotments, limit off-roading, cover landfills and close trails.

Some pieces of the 6.4 million acres of BLM land designated as critical habitat in 1994 have changed jurisdiction since then, including millions of acres transferred to the National Park Service. Most critical habitat remaining under BLM management now has special protection as "areas of critical environmental concern" or "desert wildlife management areas"; in the latter, development is limited to 1 percent of the total area. The USGS and FWS are working with energy planners to retain wildlife corridors between critical habitat areas. And yet, according to a 2012 study in BioScience by Averill-Murray and others, the "effectiveness of most recovery actions is … unknown," and in many parts of its range, the tortoise continues to decline.

"If we don't get serious about taking away some of the stressors on tortoises," says Anderson of the Center for Biological Diversity, "they may go extinct. We need habitat where the highest priority is desert tortoise conservation and where we can remove the other threats." She ticks off the big national parks, none of which are really prime tortoise territory: Death Valley is too low and too hot, while Joshua Tree's most suitable habitat is too accessible to humans, and the Mojave National Preserve allows grazing. The animal's best hope, she says, can be seen at the Desert Tortoise Natural Area that Berry helped found. It's fenced off and entirely dedicated to tortoises; other uses are excluded, including off-road vehicles. "Data from there show tortoise densities much higher than in critical habitat managed by the BLM next door," she says, citing research being done by Berry and others. "(Their) study will provide a compass on how to manage for tortoises."

And Fort Irwin, perhaps, provides a "how not to" for tortoise management. Five years after the 158 healthy tortoises tagged for Berry's study were moved, she says, "84 are dead. Another 21 are missing. Six or seven of those, we're sure they're dead. We found chewed-up transmitters."

She will track the survivors through the bleak hills near Barstow to get a long-term picture of their survival rate. For such long-lived animals, five years of living after being uprooted might still end in slow starvation, or they might genuinely be re-establishing themselves. "We still don't know if translocation works," Berry says. "We need long-term studies. We need numbers."

Even if translocation techniques are improved, she firmly believes that the best thing that can be done for the desert tortoise is to leave it alone. And in the most protected areas, that might happen. But elsewhere across a 48,000-square-mile desert, it seems inevitable that tortoise-moving will continue. For Berry, every inch a product of the late-'60s ecology movement, it's intolerable to contemplate that the animal she's devoted her life to might become dependent on the kindness of rangers.

Berry continues gathering data from her plots and transects across the Mojave and part of the Sonoran deserts. By the time she retires, says her boss, Steve Schwarzbach, her life's work will appear in what he calls her "masterpiece": the longest, most extensive survey of the animal's demographics and survival rates ever done, and a mighty study of the tortoise's passage into the Anthropocene. His provisional title for it: "The 40-year decline of the desert tortoise."

Yet when Berry is asked if she gets depressed chronicling the disappearance of an animal older than recorded history, she seems surprised. Then, in her flat, matter-of-fact way, she replies, "People like myself, the best we can do is present the best possible science and be an advocate for its use. I don't allow myself to get depressed because it takes up time -- and I don't have that much left."

Award-winning reporter Emily Green is an environmental writer based in Los Angeles. She blogs about Western water at www.chanceofrain.com.

This story was funded with reader donations to the High Country News Research Fund.

© High Country News

This article originally appeared in the Aug. 5, 2013 issue of High Country News (hcn.org)

Definition of an Endangered Species

Agassiz's desert tortoise is now on the list of the world's most endangered tortoises and freshwater turtles. It is in the top 50 species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) Species Survival Commission, Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, now considers Agassiz's desert tortoise to be Critically Endangered (Turtle Conservation Coalition 2018).

The IUCN places a taxon in the Critically Endangered category when the best available evidence indicates that it meets one or more of the criteria for Critically Endangered. These criteria are (1) population decline - a substantial (>80 percent) reduction in population size in the last 10 years; (2) geographic decline - a substantial reduction in extent of occurrence, area of occupancy, area/extent, or quality of habitat, and severe fragmentation of occurrences; (3) small population size with continued declines; (4) very small population size; and (5) analysis showing the probability of extinction in the wild is at least 50 percent within 10 years or three generations.

In the FESA, Congress defined an "endangered species" as "any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range..." The California Endangered Species Act (CESA) contains a similar definition. In CESA, the California legislature defined an "endangered species" as a native species or subspecies of a bird, mammal, fish, amphibian, reptile, or plant, which is in serious danger of becoming extinct throughout all, or a significant portion, of its range due to one or more causes (California Fish and Game Code § 2062). Given the information on the status of the Mojave desert tortoise and the definition of an endangered species, The Desert Tortoise Conservancy believes the status of the Mojave desert tortoise is that it is an endangered species.

The IUCN places a taxon in the Critically Endangered category when the best available evidence indicates that it meets one or more of the criteria for Critically Endangered. These criteria are (1) population decline - a substantial (>80 percent) reduction in population size in the last 10 years; (2) geographic decline - a substantial reduction in extent of occurrence, area of occupancy, area/extent, or quality of habitat, and severe fragmentation of occurrences; (3) small population size with continued declines; (4) very small population size; and (5) analysis showing the probability of extinction in the wild is at least 50 percent within 10 years or three generations.

In the FESA, Congress defined an "endangered species" as "any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range..." The California Endangered Species Act (CESA) contains a similar definition. In CESA, the California legislature defined an "endangered species" as a native species or subspecies of a bird, mammal, fish, amphibian, reptile, or plant, which is in serious danger of becoming extinct throughout all, or a significant portion, of its range due to one or more causes (California Fish and Game Code § 2062). Given the information on the status of the Mojave desert tortoise and the definition of an endangered species, The Desert Tortoise Conservancy believes the status of the Mojave desert tortoise is that it is an endangered species.

Habitat restoration

In addition to supporting research to understand how invasive species affect desert tortoises, the Service is also working with other agencies to save the species by improving its habitat. The habitat restoration process is a two-pronged approach that includes herbicides and out-planting.

“We are looking to do some experimental restoration treatments that will help us learn how to restore desert tortoise habitats that are burned,” says Sara Scoles-Sciulla, plant ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey.

There's much to see here. So, take your time, look around, and learn all there is to know about us. We hope you enjoy our site and take a moment to drop us a line. The first prong involves knocking back the grasses. With two treatment types, the herbicides are designed to protect against the invasive species of grass. First, a pre-emergent herbicide targets the grass before it has an opportunity to germinate from a seedling. Second, a post-emergent herbicide targets the plant once it has sprouted. The specialized treatments are designed to cease the reproduction of additional foreign grass and allow the ecosystem a window for native plants to grow back without the competition.

“[The herbicide is] non-selective,” says Maura Schumacher, biological science technician at the National Park Service. “Wind and rain will cause this herbicide to get to the non-target areas and kill non-target native desirable species. We're very careful with where the herbicide goes, when we're spraying it, what time of day … so we can preserve the native vegetation.”

However, since so much of the Mojave Desert has already burned, there are not enough native seeds left to take advantage of this window. This requires the scientists to apply additional remedies in the second prong of the restoration strategy. Scientists administer treatments like seeding and out-planting greenhouse-grown native species. The scientists also rely on desert rodents to help the process along by fertilizing and dropping the seeds all over the Mojave.

“Once [native shrubs] are back on the landscape, we think they will provide the shade, and they’ll provide the structure for tortoise burrows that are necessary to keep this endangered species going out here on the landscape,” says Jonathan Smith, restoration project manager at the Bureau of Land Management.

“We are looking to do some experimental restoration treatments that will help us learn how to restore desert tortoise habitats that are burned,” says Sara Scoles-Sciulla, plant ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey.

There's much to see here. So, take your time, look around, and learn all there is to know about us. We hope you enjoy our site and take a moment to drop us a line. The first prong involves knocking back the grasses. With two treatment types, the herbicides are designed to protect against the invasive species of grass. First, a pre-emergent herbicide targets the grass before it has an opportunity to germinate from a seedling. Second, a post-emergent herbicide targets the plant once it has sprouted. The specialized treatments are designed to cease the reproduction of additional foreign grass and allow the ecosystem a window for native plants to grow back without the competition.

“[The herbicide is] non-selective,” says Maura Schumacher, biological science technician at the National Park Service. “Wind and rain will cause this herbicide to get to the non-target areas and kill non-target native desirable species. We're very careful with where the herbicide goes, when we're spraying it, what time of day … so we can preserve the native vegetation.”

However, since so much of the Mojave Desert has already burned, there are not enough native seeds left to take advantage of this window. This requires the scientists to apply additional remedies in the second prong of the restoration strategy. Scientists administer treatments like seeding and out-planting greenhouse-grown native species. The scientists also rely on desert rodents to help the process along by fertilizing and dropping the seeds all over the Mojave.

“Once [native shrubs] are back on the landscape, we think they will provide the shade, and they’ll provide the structure for tortoise burrows that are necessary to keep this endangered species going out here on the landscape,” says Jonathan Smith, restoration project manager at the Bureau of Land Management.

Additional Ways to HelpThere are ways the public can help the desert tortoise. First, be extremely careful with sparks or fire in the desert to avoid causing a wildfire that can quickly get out of hand. If you see a desert tortoise, the most important thing you can do is not touch, harass or pick it up unless it immediately needs to be moved out of harm’s way.

While they might look friendly, approaching a tortoise might scare it and cause the reptile to empty its bladder, losing the liquid it needs to stay hydrated in its harsh climate. Another way to help the tortoise is to be cautious when traveling through its habitat: check under parked cars prior to ignition as tortoises might seek shade under cars; stay on marked paths while hiking to avoid disturbing its burrows, food or shelter; and drive slowly on designated routes to avoid crushing the tortoise. |

In addition, desert tortoises have charismatic personalities which can entice people to pluck them from their natural habitat. Roy Averill-Murray advises people against taking tortoises they find home with them.

“It is really important that [people] do not collect tortoises from the wild; the population is too low and can’t sustain that,” he says.

Likewise, do not release pet tortoises because they can spread disease to wild tortoises.

The public can help the Service and its partners save the desert tortoise. Human activity caused the species population to decline, and human activity can bring it back.

“It is really important that [people] do not collect tortoises from the wild; the population is too low and can’t sustain that,” he says.

Likewise, do not release pet tortoises because they can spread disease to wild tortoises.

The public can help the Service and its partners save the desert tortoise. Human activity caused the species population to decline, and human activity can bring it back.